“It Isn’t Always Fun.” – Australia. A Mini Sabbatical

Shortly after separation from Nelly, in fall of 1982, I left Minneapolis for a much-desired quarter leave at the University of Sydney, Australia. Following a lecture stop with Mack Smith in Taipei, I continued to Sydney for an extended visit with Stewart Truswell, a medical nutritionist I had met in London and whose work I had long admired. There I set out to collect material on the Australian aborigines and to gather thoughts for a more scholarly and broad synthesis of the ideas I had long explored as a hobby, ideas about evolution and culture in the genesis of heart attacks. At the time, our community studies in Minnesota were well-launched and strongly led by Russell Luepker and Ron Prineas, who also held administrative roles as Associate Directors of the Division. The complicated merger of Physiological Hygiene with Epidemiology was still a year away. So it was “now, or never,” my Sabbatical. I flew off to Australia with a light heart.

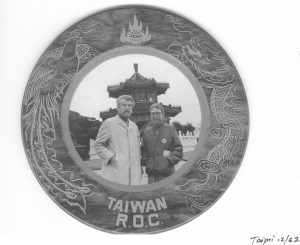

Mack Smith and the author in Taipei

Sydney, December 11, 1982

Sydney’s bold sensuality is breathtaking: open sky above an immense, magnificent harbor; friendly people in the streets; lovely buildings and beaches in every vista; and jazz, jazz, jazz everywhere, every day and every night.

Sydney is a lovely molding to the hillsides above a shimmering harbor.

Sydney is a delicious anomaly with its hot, dry days and cool, breezy nights and every-evening thunderstorms. It is June, you know, in December.

Life in the Women’s College dormitory is, however, sterile. Most students here for the winter (our summer) quarter are English and never speak to anyone. In contrast, the Aussies usually know your life story within a few minutes.

I am quickly established in the department of Stewart Truswell, who is a charming gentleman, close to my age but younger, leading an active human nutrition section in the division of biochemistry. We hit it off well though we had known each other mainly by reputation before I invited myself to visit. He, too, has recently separated from his wife, and we have common interests in nutrition and anthropology. Morning sessions with him are a pleasure. When I complained I was getting so much attention and faculty privilege and doing so little for it, he replied, “Nonsense, you’ve already been extremely stimulating for me.”

Schedule

First off is a delightful walk from Women’s College through a back gate, a wander through the formal grounds of St. Paul’s College, out the main University gates and across an overhead bridge to the modern part of the campus. There I work until 10:30 or so and then take morning tea with the nutrition faculty. I may go for late tea with the Epidemiology faculty in the Commonwealth Building and remain there for faculty lunch. I’ve proposed to Stewart that we do blood alcohol “tolerance” curves to see whether there are differences in clearance among those who have their pint for lunch and get sleepy and fade, as he and I, versus those who steam away effectively throughout the afternoon!

In mid-afternoon I am liable to get a call from cardiologist friend, David Kelly, announcing that he has “birds on the string” and that we should meet at his sailing dock in half an hour. I accept happily, on the condition that he can deposit me, or the entire sailing party, at whatever jazz pub by opening time, 7:30. Pubs close at 11. Then it’s early to bed to read. It seems I must have needed this bout of freedom and repose.

Little wonder that my writing output the whole two months was only a couple of editorials, one translation from the French of an old expedition to Timor and Australia, plus this lengthy journal-travelogue. I failed heavily of a hoped-for book draft on evolution, culture, and heart attacks!

Sydney Scenes

Ferry and Clamshell

Sydney Beaches

My Hotel-Apartment on Bradley Head of Sydney Harbor

The Great Sydney Ferry Race January 17, 1983

One week into my sabbatical in Australia I have had rich conversations with Stewart Truswell, met with bright young epidemiologists at the Commonwealth Institute of Health, and determined the key people in Newcastle and Canberra who will have similar interests, on the one hand, in community health promotion and, on the other, in the diet of early humans. I have read a whole series of articles from the innovative work of Truswell’s group and made a new draft of an editorial on “Sources of Diet-Heart Controversy, Part I, The Shape of the Cholesterol-Coronary Disease Relationship.” [An issue resolved a few years later by the findings in 370,000 MRFIT screenees. The relationship is, as expected, continuous.]

I am now well into the only definitive monograph on shellfish scavenging, Shell Middens, by Betty Meehan, written about today’s aborigines on the north coast of Australia. It begins to fit with prehistory in that shellfish gathering and eating in hunter-gatherer economies apparently increased from the late Pleistocene. The example I already knew about was among the Terra Amata tribes of homo erectus on the French Riviera, evidenced by shell fragments in their coprolites (fossil feces).

The sense of her work is that humans have probably forever exploited tidal flats for a significant proportion of their food. The absence of archeological evidence may be due to the rising and receding sea levels over the eons, which either hid or destroyed the evidence. The huge kitchen-midden shell mounds found on shores around the world, particularly common in coastal Florida, date consistently from the year 8000 before-the-present, suggesting that sea level must have stabilized about that time in the current interglacial period.

Taking Stock

I have wondered whence came these ideas, which seemed to arrive serendipitously, about the maladaptations of modern industrial humans, based on their hunter-gatherer state of metabolic evolution. I am pleased to find that several people I respect highly, Stewart Truswell, Hugh Trowell, Denis Burkitt, Glen Isaacs, and Cavalli-Sforza, for example, arrive at similar, though, of course, much more informed conclusions than mine. Modern Nutritional Man may be described succinctly as a hunter-gatherer who has had far too little time to adapt metabolically to the nutritional patterns that appeared with agriculture and food technology.

I conclude that it was a very fine idea, even a brilliant one, my coming to Sydney. I have had the chance to read several books. I walk four to five miles a day and am pleasantly sun-burnt from two visits to the lovely Sydney beaches. Everyone here, medical, anthropological, and musical alike, is open, hospitable, and friendly. They invite me hither and thither. Clearly, three months here would have been better than two, and six better than three, but I am happy with what I have. It ain’t Paradise but it’s close. It’ll do for now.

Minnesota, on the other hand, seems from here to be suffering intellectual obstipation. I will try to loosen it up a bit on my return.

The Blue Mountains and Katoomba: Christmas Week

Good humor prevailed as the famous Hotel Carrington Christmas dinner closed with a serenade by a lady violinist accompanied by a spirited young pianist. The portly middle-aged musician, in bright satin gown, wearing thick astigmatic lenses and heavily henna-rinsed hair, launched into a medley of waltzes, quite competently for this level of entertainment. Then, unfortunately, she proceeded to pirouette among the tables, playing all the while, her smile a fixed risus sardonicus.

By this time, our rollicking foursome, Geoff, Lynda, Vivien, and I, were launched into a series of laughter-choked remarks on the entertainment in this country town and its 100-year-old hotel, which had all come to such a low state of grace. Our jollity was interrupted by a prominent announcement from a pinched-faced little chap who declared to the public dining room that he would be showing in the library a series of slides of last new year’s celebration at the same Hotel Carrington, along with others of his “world travels” with his wife. In our scandalous mood this was too good to resist and we took our coffee into the library. There we witnessed a classic of dowdy amateur lantern-slide presentations, with all possible faulty exposures and compositions, inane, irrelevant, out-of-focus shots. Imagine the audience: one elderly kind gentleman, 16 kind elderly women, a young couple trying hard to suppress their sniggers, and our blasé and merciless foursome out-on-a-toot.

The lecturer repeatedly interrupted his painful presentation by going to the screen, pointing, and recounting such delicious asides as, “If one pays ten dollars here one gets to leaf through the copy of all the names of the citizens of Orange who gave their lives in the great wars of 1917 and 1945.” We sat through one carousel of 80 photographs and, noting that there were three more full trays, excused ourselves. One of the presenter’s shills followed us, agitated, to the door, recruiting along the way, “Oh, but you haven’t heard their marvelous travels to Queensland and Tasmania.” We apologized for our early departure, pleading the long drive back to Sydney through the mists and the windy night.

“Strine”

My ear is not sufficiently sharp to imitate the Australian accent. The more striking aspects of “Strine” are its plosiveness, with extremely short, clipped words, and its nasality, the “i” sound of the “a’s,” and such general characteristics as speaking without moving the lips, a trait of which I have been accused. The result is that I must ask for directions or comments to be repeated more often than not. Generally, I find the Aussie language unbeautiful. Fortunately, this generality fails on hearing the pleasant lingual sounds of an educated Australian woman.

Does “degeneracy” of a language with respect to its original have to do with the character and educational level of the primary emigrant population? One might think, for example, that Quebecois French is a gross distortion of Middle-Ages French as spoken, say, in the Loire Valley. Might this be attributed to the absence of educated persons among early French emigrants to North America or to the isolated educational efforts of a few priests, probably themselves of simple origins? Similarly, in Australia, the deprived, if not depraved origins of the criminal white elements that peopled that continent after 1788, and the low proportion of the population that has studied abroad, may have had something to do with the deterioration of spoken English in Australia. It is quite on a par with carelessly spoken back-country American English but even less pleasant to my ear!

Soon I will launch into anthropological explorations, studying Aborigines’ eating and activity patterns. The idea is not that modern humans ought return to hunter-gatherer subsistence lifestyles, or even to relate findings among hunters and gatherers directly to the modern state. Rather, the rationale is to find evidence from the past that leads to understanding of the present and providing hypotheses that can be tested.

New Year’s Eve, 1982

New Year’s Eve in Sydney can be compared to the Fourth of July at home in its turn-out of the masses and in the festive spirit of mid-summer. It culminates in a magnificent fireworks display at midnight. The view over Sydney Harbor from the Bowman family apartment is incomparable. On our far left is a long line of residences and harbor industrial activities leading eventually to the south head of the bay. Immediately leftward is a peninsula, Bradley’s Head, on which the zoo is situated and at which point the harbor makes a major L-shaped turn toward the heads. In full frontal plan, looking westward, is the skyline of downtown Sydney with its pinnacle, the space tower, shining brightly through low scudding clouds. In the fore plan are myriad ships, large and small, ferries, sea taxis, and hydrofoils, criss-crossing in the reflected light of the city. The magnificent Opera House dominates the city view.

To our right is the Sydney Harbor Bridge, tonight illuminated in turquoise and green, and to its right is the agglomeration of North Sydney with its dull cubic skyscrapers all brightly lighted. In the immediate fore plan below our balcony are charming turn-of-the-century houses with palm trees, hydrangeas, honeysuckle, and winding hilly streets leading abruptly to the harbor edge. New Year’s parties are underway beneath tarpaulins because of the threat of thundershowers. Gaily decorated, brightly lit water craft ply back and forth in the harbor, celebrants packing fore and aft decks. An occasional chartered ferry steams by with the flashing lights of a disco within. Laughter and wild “yippees” rise from all round in a crescendo building toward midnight.

On our commanding balcony, we sip 25-year-old Irish

Whiskey as Dame Mae Bowman, who is of a 75-year Irish vintage, regales us with one delightful story after another of pioneer days in Adelaide.

As the magic hour of the New Year approaches, I serve my treat of hard-boiled eggs filled with caviar and we munch peppercorn cheese or homemade pâté on British water crackers. The cork of my bottle of Piper-Heidick is recalcitrant and I fail to extract it until midnight is past.

The fireworks display originating from the park to the south of the Opera House is superb; brilliant spirals and streamers and varicolored starbursts within starbursts; the highest and brightest magnesium flares and streamers; climaxing in a mighty boom! at 12 minutes past the hour.

According to our hostess, there has not been a finer display, with the possible exception of the one given Queen Elizabeth on Australia Day many years ago.

Gravity

The morning in Sydney is sunny and sultry. Do you ever have an impression as I do that the force of gravity varies? There are days when one is insufferably heavy, leaden. Lying down, gravity tugs at the whole body and it is difficult to rise. Walking on the level, one feels weights at the ankles, the knees, the hips and the lower back. Walking up an incline, the muscles send signals they are working harder than usual. One wonders, on such a day, how the heavy clod of humanity ever evolved to stand upright and prosper against such an oppressive force. Contrast this feeling to another day when one rolls out of bed with a lightness of being, an ease and vigor of motion, almost an illusion of weightlessness!

Today is a heavy day, when every step is forced against cruel, demanding gravitation.

’Tis only in summer when one can be animal, not be an animal, but be animal, as in human animal. To sigh, to yawn, to stretch, to doze, to drink, to eat, and to lie languidly, thinking nothing at all, till shortly the animal is again aroused — to sigh, to yawn, to stretch, to doze, to drink, to eat, and to lie languidly, thinking nothing at all, nothing at all.

A “Cat-and-the-Fiddle” Night to Remember

Pubs are found on almost every corner in the suburbs of Sydney, but the “Cat and the Fiddle” is uniquely situated on a point jutting into the harbor. Geoff Bull has designed a bandstand there that stands six-feet high and well above the crowd, allowing the music to project over all as the musos avoid the bustle and bumpings from celebrants and dancers. One side of the pub is occupied by two billiard tables that click away during the music and on the other are tables for the jazz aficionados. In the back of the bar are stools for other jazz lovers to perch. The regular pub folks chat away endlessly, turning their attention to the music only when it tends toward the frenetic.

The musicians “come to play” at the C. and the F., where the sets are intense and numbers are played back-to-back. Geoff Bull is such a natural musician that one can suggest a tune no one in the band except him knows and in a minute or two he writes out the chord structure and puts the whole in front of the rhythm section. We can then take off on such obscure numbers as “Blues In My Heart”, or “Old Stack O’ Lee Blues” and make a decent presentation on the first go.

After a steaming-hot last set we close at 11 p.m. and depart with friends and followers for the post-jazz-festival celebrations at a hall on the harbor near The Rocks. Those from my memorable first visit to Berry Island in the harbor in 1977 are there, including two elderly rangers from the Snowy Mountains who do remarkable jigs. Young ladies in the crowd, mostly wives and companions of the jazz musicians, seek out the older men for dancing, apparently because of the originality of their steps. They seem to regard this an opportunity to learn innovative steps rather than slumming with outdated citizens. I find that nice.

Transported

Geoff Bull’s companion, Lynda (now his wife), and I danced together as the pulse of the evening rose. It seemed for a short period that I could do no wrong and that dear Lynda, who has been such a friend, could respond perfectly to my eccentric, unconfident rhythms. It almost seemed momentarily as if I were a dancer, so much the conviviality and swing transported us. I was dumbfounded to be sought after immediately by the companion of another friend, a bass player. She approached, slipped off her pumps, and confronted me saying: “I don’t know you but you’re dancing beautifully and you must dance with me!” How could one refuse? We performed with suitable abandon as the band swung into the final set. [Well, once in a lifetime a dancer is better than never!]

Our cozy group then hefted the cooler outside the steaming hall onto the green where many stopped by to join us in the breeze. They talked about the visiting Englishmen and questioned me about my Beuscher, Martin, and Conn soprano saxophones, their vintage and individual qualities. Their curiosity and scholarship about jazz are impressive. Apparently my uniqueness to them is having roots in the South and in New Orleans and, thus, origins in the music they love.

We are bathed here in Sydney in a warm comradeship, a common bond of New Orleans music, of people and cultures and musical eras, in sounds, in rhythms, and tonight, miraculously, even in the dance!

I suspect that dancing to jazz and rock is the modern counterpart of the social dances central to the lives of our hunter-gatherer ancestors, enriched today by harmony and technique and modern instrumentation while impoverished surely by loss of the complex rhythmic sense that so powerfully swayed our forebears. In the open culture of Australia, with its sensuality and closeness with nature, one feels a greater kinship with the evolutionary past. I feel grateful to be where this kinship can be expressed. Australia’s beautiful sounds and powerful rhythms enjoin the simple glories of living.

Newcastle. A Different Sort of Medical Education

I have just visited Newcastle, a provincial, industrial town of coal and steel manufacture on the east coast, 100 miles north of Sydney at the mouth of the Hunter River and the famous Hunter Valley northern wine region of Australia. I was invited by Stephen Leeder, a charming gentleman in his early 40s, who is Professor of Medicine and Community Medicine at Newcastle University, a graduate of the medical school at Sydney, and a Ph.D. in epidemiology from Sydney. He also has studied with Walter Holland at St. Thomas’s Hospital and with David Sackett at McMaster, having impeccable epidemiological and clinical credentials, therefore. In addition, he is an education activist and intellectual who has joined a group of leaders of this new medical school graduating its first class. As far as I know, it is the only institution that has dramatically overthrown traditional medical education for a problem solving approach, starting out in the first year. The end results are yet to be determined.

There was much talk during my visit of the difference between the Sydney, Melbourne, and Newcastle medical schools, with the latter’s integration of clinical studies from the first year and where, because of this, the new house staff is at a distinct advantage over the graduates of other schools. Nick, one of the Sydney medical students soon to intern in Newcastle, remarked on the absence of scientific theory and method in his medical school and the absence of critical skills in evaluation of patients and of the literature. Rote memorization and the lack of problem-solving or scientific method appear common throughout western medical training. I suspect this can be partly attributed to the large size of classes, which requires mass lecturing, mass-produced and mass-graded examinations, and student anonymity, in contrast to the close identity, direct confrontation, and intellectual challenge of the classical university.

But the characteristics required of a popular medical lecturer in Newcastle are the same as elsewhere, that the individual be young, attractive, modern, technologically oriented, enthusiastic, and well-organized, in contrast to being thoughtful, probing, problem-oriented and dealing in decision-making logic. In traditional training, of course, the latest facts and pearls of wisdom are the sole desideratum!

The concept as well as the content of the Newcastle curriculum is impressively liberalized, designed to stimulate students in small groups to achieve a unique educational experience. The curriculum almost totally rejects formal lectures, the “spilling out of teachers’ outlines onto students outlines.”

Today I continued my discussions on the curriculum and met the bright young dean, Geoffrey Kellerman. My hour-long presentation on the background, design, rationale, and experience of the Minnesota Heart Health Program was well received and I fielded many questions about Minnesota methods and experience. They also quizzed me about the political effect in the States of the “negative” results of the MRFIT trial and about the current backlash from unsuccessful interventions in trials among middle-aged, high-risk men.

Telecommunication?

The clinical electives available to medical students at Newcastle Medical School include the Aboriginal Medical Service. A young colleague, Nick, described his experience with the purportedly mysterious transmission of messages over large distances by the aborigines:

It seems that Nick’s assignment was to a mobile clinic for lepers, where he was responsible for giving a series of scheduled antibiotic injections. On a particular morning, literally nothing went right, needles broke off, medication was poorly delivered into the syringes, his technique was atrocious, and the day’s activities could only be described as a therapeutic disaster. The next day, at a site more than a 100-mile drive away, he was to conduct the same sort of clinic. In he walked with his senior colleague to find a room full of aborigines waiting for their periodic leprosy injection. He proceeded to the office to obtain patient records and don his white coat. When he emerged, the waiting room was empty. Knowledge of his lack of prowess had preceded him over the many miles over the night, without benefit of telephone or radio or other vehicle.

The anthropologists I read and talk to here seem to reserve maybe a tiny corner of potential for communication beyond currently understood phenomena. However, several pages in the book by Blainey, “The Triumph of the Nomads,” speak of great skills in communication by smoke signals, which, in the absence of an African-type drumming culture seems the more likely explanation in Australia. Consider its back-country of vast plains and clear skies, its balmy weather, quiet wind-free mornings, in a culture where young and old tribesmen carry fire sticks at all times and have the potential to start blazes and send smoke signals at will. Their ability to transmit descriptions of the size, direction, and rate of progress of both people and animals is well documented. Thus, it seems likely that aboriginal tribes whose hunting lives depend on foreknowledge of movements and weather changes should have highly developed modes of observation and communication. These seem supernatural to us only because they are beyond our ken.

The Great Annual Sydney Ferry Race

Today was the more glorious of my entire musical existence. It was a day with Geoff Bull’s band on the Karabee Ferry, one of six ancient ferries operating around Sydney Harbor for the Great Annual Sydney Ferry Race, a part of the New Year’s and Australia Day celebrations and a splendid tradition. Some of these charming old ladies were actually sailed down from England to Australia in the early days of the century and they still offer service between suburbs fronting on Sydney Harbor. On this day, each ferry is sponsored by a local industry. Our lady, the Karabee, for example, is paid for by the natural gas company and all passengers aboard, a crowd of a couple of hundred, are invited for the “race,” a free bar, picnic lunches, and continuous Jazz!

We plied the harbor, blue smoke billowing from our smokestacks, red from others, yellow from others, with blue balloons released from our upper deck at intervals between gay soundings of the steamboat whistle. We sailed from the pier at Circular Quay next to the Sydney Opera House on this sunny Sunday morning and approached the starting line under Harbor Bridge. Literally hundreds of motorboats and sailboats plied along our course while we were escorted by police boats. Tens of thousands of people on the various promontories of the bay watched the event. Helicopters, airplanes, and blimps flew above, on this bright and happy day, temperature about 75 F., with brisk winds and choppy seas.

Danny Moss from England was with us, a warm, 55-year-old, bearded hulk, a superb tenor saxophonist of the grand school that cuts across all musical ages and disciplines, a man who enjoys good music of whatever idiom, and who “comes to play.” We were three saxophones, Tom Baker, Danny Moss, and myself, with Geoff Bull swinging it all on trumpet, plus a superb rhythm section of Dieter, bass, Laurie, drums and Graham on guitar. Wow!

One could see the old six-cylinder engine laboring below decks and though we sailed full throttle the whole afternoon we came in only fifth out of six in the race. Never mind. Often we ran neck and neck with the other old ferries and with loud cheering we would pass them up, then they would pass us — all with boisterous gesticulations, TV cameras rolling, helicopters zooming, and police boats darting in and out to shy off Sunday sailors from our ponderous wakes.

Under the lovely slow roll of the deck we played delicious blues all afternoon: “Fat Man Blues, Creole Love Call, Old Stack O’ Lee Blues.” There was no room for dancing and only a small appreciative audience confronted the band. Most folks stood on the outer decks, waving and cheering and following the harbor scene. We simply rocked away, playing fine, close-harmony riffs, listening to and stroking each other.

Little kids on the excursion would appear for a moment before us, just when we were able to hit a loud, low A-flat to blast their ears and watch their eyes pop in delight. [Jazz always strikes a sensitive chord in children and other good hearts.] Everyone played in a restrained but swinging fashion, without frantic rushing , no tune too fast or too loud. Between numbers, the musicians’ anecdotes and gentle, witty characterizations of colleagues around the world were affectionate in the telling.

I had a sense that we found on this day a little moment of jazz history — transcendent, fundamental, universal, and oh, so sweet. To be a part of this band on this magic day and to receive the warm support of magnificent musicians (for example, in the midst of my solo, to hear Danny Moss murmur, “Love you man, love you man, you’re doin’ it!”). How could one fail to play well or not be supremely happy.

A blue-green wake parted behind us and rushed madly toward the shore, spreading waves of happiness across this blessed sunny land.

January 16

Sunday night at the Cat and the Fiddle Pub, all of us refreshed after a long sleep following the ferry race, the Bull band gathered with its sweet “band followers.” It literally “jumped” from the first note. As we climbed on the stand for the second set, Stewart Truswell came in with his lady friend, Cathie, and his older son Paul, also with his girlfriend, and a younger son, Andrew, who is musical. Again, the band swung hard: “Maryland, My Maryland, Way Down Upon the Swanee River, Creole Love Call, Boogie Woogie,” and on and on.

The pub tables responded, particularly that of our friends who seemed to immerse themselves in the songs and in the pleasure we were having playing together. Across the stage front, Tom Baker, Marty and I were on sax. Geoff’s horn was pointed toward the sky. The rhythm section of Peter Clohsey, Paul Baker, and Dieter Vogt was especially driving and responsive. [In the fall of 2001, the world of jazz was shocked by the sudden, unexpected death of Tom Baker, superb master of many instruments, due to a ruptured aorta (a congenital defect), in Europe following the Breda Jazz Fest. It is reported that he left his collection of instruments to friends before departing on tour, saying they were theirs if anything happened to him!]

We closed what has been my best week of jazz ever, with the warmth of fellowship, the glow of creation, and the response of friends. We embraced each other in the cool evening air after the early pub closure and went our separate ways, toward other “Down-Under” adventures. Australia, thy name is Hedon.

January 18

Tonight we attend Dame Joan Sutherland in Fledermaus at the Sydney Opera House. The group will be Stewart and Cathie, who is a medical student in her early 30s, with whom Stewart has written a book, and me with my frequent companion, Vivien Bowman, daughter of a former Department of Agriculture official. Both women are bright, articulate, and enthusiastic. They do the heart good, even if for me it’s only for a short, sunny holiday from a complex, harried, and somewhat melancholic life these days. [I speak only for myself, not for Stewart.]

Coming up on the morrow is a trip to Canberra for a visit with anthropologist Rhys Jones and his staff, and thence, if weather and deerfly populations permit, and all else falls into place, it’s off for a three-day camp in the Snowy Mountains (as in, “The Man From Snowy River”). [May I remind all that you must see two films, if you have half a chance, “We of the Never Never,” and “The Man From Snowy River,” for their simple delight and to understand pioneer Australia.]

January 20

Anthropologia

Today was one of the more exciting days intellectually of my time in Australia. Rhys Jones, Welshman, in his early 40s, is stocky with a slight beer belly, florid, lightly bearded, restless, and articulate, in fact, a non-stop talker. He is a man of ideas, rather full of himself but with an appropriate awareness of his intellectual position. He makes the sort of dry, witty criticisms of colleagues that put things into clear perspective. For example, he said that I must read and meet Peter White: “In a particular article in the journal Prehistory he will refer to me 42 times, all 42 of which are uncomplimentary. Thus, we beg to differ, but you, nevertheless, must read him.” Compare this attitude to the low intellectual content of criticism in which some academic colleagues at home engage, insinuating, self-centered, personally defamatory. I prefer this way of the lively and honest scientist rather than that of the wily and devious street fighter.

Rhys Jones draws diagrams to illustrate his every idea. Even during lunch he drew a diagram of the course of his skills with increasing concentration of blood alcohol. In these he observes first a rise and then a fall in creativity as he drinks, experiencing a progressive flight of ideas that is gradually focused until extraneous things “dissolve” and he reaches, he claims, an intense level of productivity, which soon falls off rapidly. [I call that a powerful rationalization for mid-day drinking!]

Similarly, he diagrammed population growth and constantly drew maps and graphs, some of which were three-dimensional. I suppose this is helpful for one with such a rich, multidimensional thinking pattern.

Betty Meehan has characteristics I find common to female anthropologists: calm, directness, orderly thinking, commitment, sincerity, integrity, attention to detail, and identification with “the underdog.” She is fortyish, with straight plain hair and sharp Anglo-Saxon features, robust proportions. She speaks of “we” when referring to Rhys, so I assume that they are companions or married; their field work together began in 1972. She was pleased with her new book I just finished reading on shell middens, which is indeed attractive and readable, one of the finer combinations of quantitative anthropology and good narrative description.

With her firm base, going back to 1958 as an undergraduate, she has close friends among the Abo tribes. With long experience she is efficient in updating her data to fill in gaps and describe changes over time. She suggests that she has enough data for a half-a-dozen such books.

Other anthropologists throughout this land appear less fortunate in their rapport with the aborigines. Indeed it appears that all new field studies are in abeyance pending resolution of major issues between the aborigines and the white government. This has apparently not affected Meehan’s work and plans. She finds herself among a new group of archeologists who, as she describes it, comprehend how little valid interpretation can be made of artifacts in the absence of understanding, derived from peoples still observable and living a lifestyle resembling that of prehistory.

I quote the elegant last sentence of her monograph to show the thrust of her interests: “The ubiquity of shell middens around the coasts of the world may indeed be testimony to the special supportive role of shellfish in coastal economies and be recognized as sitting monuments to yet another unappreciated contribution made by women to the maintenance of human society.”

Clearly she is a leader of a “feminist” view that endeavors to reconstitute a balance among what should be obvious: Humankind survived and thrived because the sexes successfully specialized and collaborated over the eons. She brings a cultural anthropological approach to archeology and prehistory, believing it important, in explaining direct observations, to “get into the head” of a peoples to know why they do things.

Rhys’s main intellectual concern at the moment is a paper he has in preparation on population control and its determinants in prehistory. As he reviewed these ideas I began to see analogies to my biological interests and to interject them from time to time. The encounter became exciting when I made a couple of suggestions that he stopped conversation to record. I recognized that his principal argument was similar to that of the Johansson-Leakey debate about labeling a fossil finding as a new species versus an example of the range of variability possible within species. And I recognized too, that his ideas about population limits might be readily confirmed by measuring the volume of shell middens.

He was quick to confirm my musing that “there must be a hunter-gatherer system” more or less common to all to be responsible for the remarkable success of the species prior to civilization. His assumptions involve equilibrium among several factors: the capacity of the people, the land, their sources of energy, and their personal or tribal “drive.”

Welshman Rhys Jones is particularly excited about working in Australia because it is the only land of hunter-gatherers that was uncontaminated until recent times by slavery or by working the fields or herding, all of which disturb the equilibrium of true hunter-gatherer subsistence living.

Plant or Animal Food Dominance for Early Humans?

Since I started dabbling in issues of the diet and activity of early humans, beginning with preparation for the Bishop Lecture of 1979, there is already a shift in the thinking of anthropologists away from plant food dominance. Referring particularly to the papers of Lee that had a such a seminal influence, Jones goes so far as to suggest, sardonically, that the Bushmen of South Africa probably had to lay down their hunting spears for Lee to take pictures of them beside their piles of mongongo nuts. He attributes the plant food emphasis of the time as a facet of the “feminist” view of paleoanthropology, a view that emphasizes the major contribution of women to subsistence economies.

Betty Meehan talks about her meticulous measurements of aboriginal women’s productivity, by observations made over a year living in one site. Women produced calories at an average rate of 1,000 kCal an hour by gathering, foraging, scavenging, and hunting. Based on a “reasonable extrapolation” of this observed rate of productivity among Australian Aborigines, she and Jones suggest that no more than 50% of calories or 60% of hunter-gatherer foods by weight derived from plant sources. In her observations among shore-dwellers, meat predominated in most seasons, to the tune of a kilogram per person per day.

I hope to meet Kerin O’Dea in Melbourne. She opines that human enzyme systems were adapted to meat and that today’s aborigines find it difficult to cope with high carbohydrate diets. She has observed that glucose intolerance found among aborigines on the high carb diets of the reservation rapidly return to normal when they resume hunter-gatherer regimens in the sacred lands of their origins. This occurs in the recent government “off the reservations” trial movement.

Fat Eating

Jones spoke of the “prestige value” of fat but agreed that the sporadic consumption of fats could in itself account for their prestige. He is, nevertheless, clearly on the side of carnivory dominating omnivory in human evolution. [Parenthetically, from my observations of the body build, habitus, and lifestyle of archaeologists and anthropologists, I note that their views about the degree of carnivory of prehistoric diets appear to be in direct relation to their gender, plus their personal mass, and their meat, cheese, and beer preferences!]

I asked Meehan about fat-eating among the aborigines. From her direct observations living with the tribes she considers it less an innate craving for fat than the native ability to distinguish plump, therefore calorie-rich animals when on the hunt. Indeed, the aborigines tend to throw away any non-fatty wallabies, sharks, rays or goannas they encounter.

She complains that most of her data on food frequency lie fallow in uncompleted tables. She couldn’t tell me, for example, how often adult men or women or children eat specific food items but estimates that on average adult men eat a stingray liver about once a week. Then they make a sauce dip out of the rendered liver, which they then circulate among others including children as a major source of energy and fat-soluble vitamins.

She speaks of the relative caloric deprivation among women who in their daily gathering give the best foods collected to the children and who labor to produce the large amounts of food required for the frequent tribal celebrations called at the whim of the men. These feasts tend to last for days or weeks, with the burden of provisions falling almost entirely on the women. The ceremonies, a focus of much tribal tradition and effort, are called whenever the tribal wise men think they should be called. Characteristically the fêtes culminate at the full moon when the tides are higher and shellfish are more plentiful, when there is more light for the ceremony, and when the environment is rendered particularly beautiful for the occasion. Meehan experienced four such major ceremonies in one tribe during the year she spent in the bush, giving her unique expertise.

We talked about clay eating, kaolin, and she was unfamiliar with the custom of southeastern American black women to eat clay. The aboriginal women, when asked why they eat clay, simply say, “Because it’s good.” She is inclined to think it “settles the stomach” as kaolin does.

We talked about storage and hoarding of provisions: large balls of dried and beaten plums are stored in trees, for example, and nuts are buried, including cyclads and palm and pandamus nuts, in holes where they keep up to three months. Her abo colleague, Nancy, periodically bakes loaves from cyclad nut flour and in one baking spree made 90 kilograms of bread which the tribe nibbled on for months without it spoiling. She maintains, however, that there is no systematic hoarding among aborigines.

When I questioned her estimates of plant food gathering, which seemed extremely low among the Anbarra people, she indicated that she customarily weighed the major foods such as yams and, when she didn’t weigh things directly as they were harvested, she made observations of their numbers and amounts, estimated their size, and then collected the items later herself and weighed them (much as we do in field nutritional surveys). This is particularly the case for fruits, nuts, and berries, which people usually eat on the run.

Habitual Physical Activity

When we discussed habitual physical activity among aborigines, I recounted to her our Seven Countries observations that peasant (agricultural) peoples around the world seem never to sweat or to work till out of breath; rather they tend to work steadily at about 40% of estimated maximal heart rate. She indicated that for aboriginal men in Australia there were only short spurts when they would suddenly chase an animal at the proper moment of stalking. Women, in contrast, engaged regularly in vigorous activities such as digging out a goanna burrow or a large yam. Here the intensity of work depends mainly, she observes, on the avidity and personality of the hunter-gatherer. Her special aboriginal friend, Nancy, for example, really “goes out after them,” and Betty has measured the amount of dirt Nancy dug with a digging stick to retrieve a yam. These and other such quantitative data define, in a time-task sense, the frequency, duration, and intensity of work.

She observes informally that men and women will, whenever possible, walk instead of run, sit instead of walk and always seek the easiest, most efficient ways of subsistence. For example, the typical aboriginal approach to paddling, she says, is to paddle furiously and then stop to rest rather than working in a slow regular pace. In general, she says, the Abo people think you are crazy if you run. After the morning’s work, whether hunting or gathering, they routinely return to camp and lie down, smoke, and go to sleep rolled in a blanket even on the hottest days.

She spoke of social classes among aboriginal women, who can be either young, unmarried, or mature women, who do almost no work. For example, older ladies may all of a sudden decide one day that they are old and simply quit doing things. Of course, the band must support them. This seems roughly analogous to the age when many Mediterranean women put on black dresses and announce, too, that they are old and then renounce usual social responsibilities.

Daily hunter-gatherer living patterns

It is Meehan’s impression that before as well as after “contact” (meaning first contact with Europeans), the aborigines were late starters in the day. Based on her experience living with the tribes, they would lie awake in the morning, characteristically grumpy, and leave on rounds of hunting and gathering only at 9 or 10 a.m., then would work until 7 or 8 p.m. Often returning after dark, they planned their itinerary to return by the beach to the light of the sea and the moon, apparently because it was more pleasant and cooler and because they thus avoided poisonous snakes. They usually collapsed for a nap and then, for two or three hours in the later evening, life in camp would become quite animated, with conversation back and forth between campsites and hearths, talk about experiences of the day, plans for the morrow (such as how they were going to secure an animal that had eluded them today). Most tribal humor is slapstick, such as who fell flat on his face when he ran after such and such a lizard.

Later, as things settled down around camp, it was not uncommon for an individual who felt put-upon by the day’s activities, either the gods had done him wrong or his colleagues had done him in, to rise to complain to the moon in a voice that everyone could hear and understand. This would create a great silence around the camp; even the dogs became silent. People would respond with apologies or explanations of why their food had not been shared, or on the contrary, turn aside the complaint with a joke that might reduce everyone to laughter. Occasionally, in a serious circumstance, a mock demonstration would arise, with clattering of utensils and spears, even spear throwing against huts with no intention of hitting anyone. At that level of tension, the women would scurry about to move axes and guns out of reach of any male who might be getting emotional. [Oh, Taliban women, how you failed your people, for the mere fear of death!] In these ways the tribe would work out conflicts.

The major celebrations of the aborigines are called koonapippi (sp?), in which the men are sequestered within hearing of the camps. Rhys Jones has attended these and recounts how the men spend most of their time lying around or sleeping. They are the possessors of all knowledge, totems, and god-given powers in the tribe. Calling for festivities is their foremost duty to the tribe; they condescend to an occasional hunting sortie from their special sequestered place.

Women, after doing all that women must do to put in order the food and the children and the campsite [and the cat], start their evening celebration by singing and dancing in their base camp, while the men call and respond from their sacred ground a short distance away. The dancing is sporadic, vigorous but short lived, with much flapping of arms and shuffling of feet during which women may dig sizable pits into the ground with their dancing. The dancing that Meehan witnessed seems in no way as intense, rhythmic, or orgiastic as described for African ceremonies. Here people may dance for hours but never all at the same time, usually in varied short-lived solo performances, and with the music being primarily oral, unaccompanied.

Genes and Evolution

We discussed my age-old questions about: “how much of the large disease differences among populations can be accounted for by different distributions of multiple-gene effects?” I can see I won’t get an answer from a population geneticist; it is a hopeless proposition until the genes or the alleles associated with such mass diseases as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease are better defined. Neither could Kirk comment on the “thrifty gene” idea, nor on the evolution of, or survival benefit to the tribe, of longevity itself. According to Kirk, random genetic drift could explain all of the group differences between the various aboriginal tribes, based on Cavalli-Sforza’s estimates of the rates of change of the standardized variance of gene frequency, that is, mu (Greek symbol) squared, over PQ, in which groups of around 1,000 or less folks that split into totally groups, would by random drift, develop, in 10,000 years, the differences found among peoples today. His estimates fit the African and Australian-Melanesian populations, sufficient to account for their extreme differences in frequency of most alleles. Superficial traits such as sickle-cell disease can vary from zero to 10% in a population within as little as 1,000 years, by Darwinian evolution. In small groups, under constant selection pressure, such superficial changes may occur in even shorter periods. [For how, and how much, consult Stephen Jay Gould.]

Rhys Jones and Betty Meehan have generalized their ethnographic analogies of diet differences into two main types, “rain forest vegetarians and Savanna meat-eaters.” Jones made the synthesis in an article called, “Struggle for the Savanna,” where he speculates on the probability that humans evolved in Africa, on the savanna and its adjacent forests, between 17 and 5 million years ago, with their concentration on the drier tropical savanna between 2 and 4 million years ago, where they hunted and scavenged a wide variety of game animals. By 2 million BP, they were occupying the savanna in southeast Asia, China, and Java, in an environmental range comparable to that of the African hominids. With the development of the stone industry around a million years ago, man extended his range into temperate climes.

He speculates on the physiological evidence that man evolved in the dry savanna, in part based on the limited cold tolerance of humans compared to other mammals. Naked man and tropical primates start shivering at an air temperature of 28 degrees centigrade, whereas Arctic animals will go down to 10. Secondly, humans have a great capacity compared to other mammals for losing heat, based primarily on the sweat-evaporation system capable of losing 800 Kcal an hour through loss of a liter of fluids. He reiterated the strong selection toward dark people in tropical savannas. Thus, humans are fundamentally highly adapted to areas high in solar radiation, temperature, and hot winds.

Jones and Schaller speculate that the relatively weak, vulnerable human species became lords of creation mainly because they were able to hunt and forage in the full light of day and heat of the sun, whereas their competitors and potential enemies were reduced in the heat of day to powerlessness, forced to lie quietly in the shade. He extends this speculation to physiological constraints to development of the human family — within range of waterholes. All of which speculation helps put a lot of things together.

All thinks considered, Rhys Jones is highly quotable: “If the mark of man is the sweat on his brow, it is also the tools in his hand. Three tools, in order to cut, to dig, and to burn, may have been the ones that propelled man on his evolutionary trajectory.” Cutting to get at flesh, digging to get at plants and to get to water, and burning to increase productivity of the land (when done properly at the right season). These simple portable tools made man free and led to the cultural evolution of agriculture.

Use of Fire

We discussed the unique practice of the aborigines of Australia in torching their landscape. This was noticed from the time of the earliest European sailing visits. One has only to experience an Australian summer, as I have the last three days, the blistering hot desert wind sweeping into a low pressure area at 30 knots, to understand how devastating the deliberate or accidental lighting up of the grasslands might prove. [Subsequently much of southeastern Australia burned over the winter. And in winter 2002-3, the flames reached Sydney suburbs.] In the journals of many ship captains, including Captains Bligh, Cook, and Tasman, there was commentary on the presence of fire on shore at night and fires and smoke over the whole landscape they saw sailing down the Australian coastline.

It was Captain Cook’s putting ashore at Botany Bay that documented the aborigine’s unique carrying of lighted sticks and their nurture and transport of a small patch of fire built on wet clay at the bottom of their canoes. Natives were seen by Englishmen to set fire casually to little tufts of grass or bark as they walked across the land. Early Europeans observed wide areas of blackened countryside and described some of the valleys as infernos on summer days. They speculated whether the natives were incapable of making new fire and thus preserved it by carrying it around. Lighted sticks appear in some tribal groups even in times since the European invasion, but there is sufficient evidence that they made fire originally by the usual means devised over the centuries, including rubbing wood against wood.

It appears that fire was central to the way of life of the Australian aborigines and affected much of their activity as well as profoundly affecting the ecology. Though it was a principal technology of the native Australian, fire was, according to Blainey, “sometimes master as well as servant.”

I learn with sadness, from Stewart Truswell, that this vigorous, vital man, Rhys Jones, has recently departed prematurely, apparently from leukemia.

New Digs

I walk through bayfront park toward the Opera House and Circular Quay, from which I will take a ferry to the zoo and my new residence. Actually I reside several hundred yards above the zoo on Bradley Point, and took this new residence, in what is called a private hotel, to give the last weeks of my stay a little more, shall we say, light and color. It is in a large private residence the size of a mansion on Summit Avenue in St. Paul and supports the older couple who own and have operated the home for 30 years. It has a lovely glassed-in front porch with pleasant bright furniture and a big orange tabby cat looking much like Chablis. A marble foyer and lovely stairway lead to four upstairs bedrooms, each of which is converted into an individual apartment. Mine is furnished with antiques, including an armoire for storage and the only incongruity in the setting is the chandelier, a cluster of Japanese lanterns.

An anteroom serves as kitchen. The beds are twins, four-posted, with a bedside antique lamp, and for my toilette I have a handsome women’s cosmetic bench. An oblong dining table sits comfortably in the alcove off a large bay window, which has French doors that open onto a veranda extending some yards along the harbor side of the house and is framed by lovely wood molding. The whole provides a delightful colonial touch to a classic view through 180 degrees of Sydney Harbor.

Just below the balcony is a Fontainebleau-style stairway leading to a green for croquet or for lawn tennis. Beyond a fence are equally handsome, slightly more modern villas, some of which have swimming pools, and beyond them the bluff drops off to the harbor. To the right is the forest of Bradley Point which is the extent of my rightward view towards Sydney and this forest borders the magnificent Taronga Zoo. Thus, I see no part of downtown Sydney but the view starts at the northern suburbs and the long peninsula that separates Sydney Harbor from Botany Bay, the place where Captain Cook claimed this coast of Australia. At one narrow point in that peninsula, one can see over the ridge and get a peek of Pacific Ocean. To the left, I see almost to the South Head and main entrance to Sydney Harbor.

By moonlight on the night I moved in, the harbor was criss-crossed by boats making black wakes in a silver sea, some slow, some fast; water taxis that buzz around with two outboard motors at a tremendous speed. The impression is of water insects scurrying on the surface of a pond. Today, a very hot Wednesday, the sea is strangely and absolutely still and there is no harbor activity in the early morning, no shipping going by, no sails out.

En route home from the university, I descend the stairs from bayside park and arrive at Circular Quay where the ferry awaits. I sit in the bow of the “Karingai,” an older ferry boat, looking out at an elegant cruise ship, the “Princess Mahsuri,” moored just below the Sydney Harbor Bridge. On my right is the clam shell of the Sydney Opera House. In the foreground is a hydrofoil approaching the docks and settling into the water. We leave the port in a neck-and-neck race with the ferry “Lady Heron,” which seems to be considerably faster than our craft, and we are quickly out into the harbor chop. To my left under the Sydney Harbor Bridge is a permanent carnival of Ferris wheels, an ornate Ottoman palace, and a paddle-wheel boat. Now we move out into the full swells in a northeast breeze that is contrary to the usual trade winds of this season. The ferry begins a delightful roll that gives a real sense of being sea borne on what is actually only a 12-minute ride from downtown Sydney to the Taronga Zoo.

I have the prospect of a long evening without responsibility to anything or anyone but myself, to read and write on my veranda, which leads my spirits to rise briskly as does the breeze that buffets my unshorn head. Without a haircut since November 25th, and with the deepest tan I’ve had since Navy days, I suspect my appearance is positively aboriginal.

Coasting Out

It is impossible to imagine a city with more amenities, greater beauty, more comfortable living or as charming neighborhoods, more favorable climate or more cosmopolitan life and culture than Sydney. Despite its four million people it’s not yet uninhabitable from traffic, poverty, or crime.

In my final seminar today at the Commonwealth Institute of Health I was relaxed and talked about what I wanted to, that is, a pot pourri of the cholesterol-mortality curve, of concordant and discordant individual and population correlations, and finally of the Minnesota Heart Health Program. There was interest in each subject and the questioning was sharp but friendly.

I have a rash of invitations this last week, for consultation, and I have the choice: continuing my merry way to achieve a greater feeling of accomplishment, wrapping up the anthropology, continuing the vacation, or responding to needs of others here. I’ve decided I will give more time to them, I suppose to leave a good taste in both our mouths and conceivably, to open the door to future relationships. [Relationships I never pursued after becoming caught up with heading Epidemiology in Minnesota. Like the book says, it isn’t always fun.]

Derniére Ballade

Early Saturday, “the happy foursome,” Geoff and Lynda, Vivien and I, took off for Port Stevens and Shell Bay, a series of magnificent harbors an hour and a half north of Newcastle on the Pacific Coast. We traveled the back way, along the ridges and in the valleys, and finally reached, on an unpaved road, the famous “Dr. Jerde’s Joy Juice Bar,” a traditional western bar that was full of vacationers on this three-day holiday for Australia National Day, comparable to our Fourth of July weekend. There a group of bikers and other families were eating fish and chips and drinking Dr. Jerde’s Joy Juice and buying it by the bottle or case. I tried only a sip; not for me in the middle of a hot day; a mixture of port and red wine, too sweet and too strong. To picture all those bikers in that heat, taking off with their cases of lemon bitters and dry vermouth, to blaze along the blistering holiday highways, aroused my middle-aged protective instincts.

We stopped here and there at provincial museums, country hotels and pubs along the way to the coast. One got a sense how the American west must have been in the 1920s and ’30s when there was still much natural beauty to find, though modern methods of ranching, mining, and farming had already begun. Many aspects of this country seem like pre-World-War II America.

Port Stevens and our special beach, Fintal, are charming, particularly because we have the apartment of the owner of the Cat and Fiddle Bar at our disposal. Fintal is a three-mile perfect curve of beach with light-brown sand, a tiny developed area at the tip, the rest undeveloped with magnificent dunes and an enticing strip of land exposed at low tide when it leads to a promontory. We dashed across as the tide was rising just to say that we had made it and then turned back as the two tides, one from the bay and one from the Pacific, joined over the spit. We escaped just as the peninsula became an island.

Back on the mainland, we turned to discover a huge red moon rising majestically over the Pacific. Then we ran, with the moon casting our shadows on the beach, to save our belongings from the rapidly rising tide. Finally, we picked our way through sea grapes and Australian pines, the moon lighting our path, from one sandy patch to another, to arrive at our cozy cabin. There Geoff, a superb cook, whipped up a Chinese wok meal that we washed down with my Christmas Beaujolais, tapped off by a mixed fruit salad of mango, pineapple, grapes, and kiwis, bathed in liqueur.

The next morning, Sunday, was bright and hot, the second day of the three-day national holiday, when we made a leisurely breakfast and took to the beach about 10. Geoff and I used an unstable child’s plastic surfboard but we both managed to catch a ride that was duly acclaimed and photographed by our bemused admirers. Our antics in falling off the board and missing waves provided howls of satisfaction to the onlookers.

We beat the holiday traffic by coming back early on Sunday, in time to play the traditional Cat and Fiddle Sunday evening job from 7-10. As usual, Geoff called tunes he knew I would be comfortable with. When the pub closes early, on Sunday, one has a sense of abrupt interruption, musicus interruptus, of an intense emotional high. But there are advantages. For us, there was a marvelous six-course Chinese dinner to enjoy and then home to bed before midnight, well stretched, parched, salted, and deliciously sated.

Closing

This is the first time I have not had to wait for a ferry to Taronga Zoo and home. I walk right on board my old friend, the “Karribee.” We sail past the Sydney Opera House in its sunny glory, its self-washing tiles glistening in the bright sunlight. A tiny water taxi whizzes by us at many times our speed. How fitting that my last happy ferry ride in Sydney should be aboard the same ship on which I spent the magnificent day of the Great Annual Ferry Race. What a day that was; what a band!

So long, mates!