“It Isn’t Always Fun.” – An Oasis in the Sahara

One of the finer adventures of “life off campus” was an excursion to Algiers on an invitation to present the population strategy of hypertension control from the Minnesota Heart Health Program. I had met my Algerian host, Dr. Feghoul, while making a similar presentation in Switzerland, where we agreed beforehand that the real wage for my lecture would be a trip to a Saharan oasis. Daughter Katia, in Europe on a Rotary Scholarship at the University of Ghent, joined me for this trip. We arrived in Algiers only a few days after I had quit Australia.

Algiers. February 14, 1983

Algiers from the air is pure white, a majestic, handsome city climbing the hillside above a graceful bay. But once on the ground it is a disaster, its chaos redolent of the anarchic Barbary Coast. A single avenue along the old Bay of Pirates carries all and sundry from the airport to and through the city. The traffic, the mass of humanity, and the pollution en route are suffocating.

The first impression of Algiers up close is one of dramatic contrasts: veiled women in lovely billowing robes riding on truck beds; BMWs weaving around goat carts, shocking incongruities everywhere of an ancient culture in rapid transition. About half the women are in modern dress, half in traditional robes with lace veils; an old woman passer-by bears an elaborate tattoo in the middle of her forehead. Only men are seen in the bars on most street corners, where there is clearly no proscription against alcohol. So far we’ve heard no attempt to explain this apparent countervailing of Mohammed’s tenets.

Children, children are everywhere; 60% of the population is under age 18. The military, too, is much in evidence; surely an oppressive burden and expense. Though our charming host, Dr. Feghoul, denies that Algeria is in a state of war with Morocco, there is uneasiness on the eastern frontier with Tunis and outright hostility on the western frontier with Morocco. The many evidences of a police state include ever-present guards in front of the diplomatic enclave down the street from our hotel and the heavy security at the airport, even on our bus traveling the mere 50 yards from the aircraft to the terminal. [The police, however, are not as much in evidence or as armed and alert as they are in the

Soviet Union.]

Soviet influence is said to have diminished here since the new president was elected and there are other signs, according to our host, of loosening control in individual rights, in commerce, tourism, freedom of movement, and, most clearly, in the rights and dress of women. The major problem of the culture, according to our host, is the age distribution and utter lack of population control. Plus the shortage of essential goods, a classic example of which happened to our host last night. Looking into the trunk of his brand new car for a spare to replace a flat after our visit to the restaurant, we found that he had none. This is not due to lack of foreign exchange (they have oil, after all); rather to the weak economy.

Promenade en Alger

Katia and I walked without a guide past the President’s Palace and the enclave where diplomats are housed and visitors greeted. It is a magnificent Ottoman building in stunning white with lovely bulbous towers and serrated balconies and artfully trimmed shrubbery and vines. I have as much difficulty describing the traditional buildings here as I did in China, being unfamiliar with descriptors for these ornate designs. One senses, nevertheless, a basic harmony between the simple and elegant structural lines and the embroidery and lattice work of the portals, windows, partitions, and frescoes.

The main palace court consists of multi-colored tile pillars supporting an octagonal dome. An incense burner is the centerpiece on the floor, around the base of which one takes tea in the heavily perfumed atmosphere. The former harem’s parlor is ornate and gracious, where now the chief wife sits entertaining guests, costumed in an elaborate, elongate silver headpiece. Furnishings include inlaid jewelry cabinets, a cosmetic dresser with mirror, myriad ornate water pipes, guitars and lyres, much blown-glass touched up in gilt, magnificent mirrors everywhere, and immense decorated shranks, all set in cool, contemplative surroundings. Each of the trunks is beautifully decorated in carved wood or paintings in the style of a particular community (e.g. Constantine, Oran, or Alger). The handsome gilt posts and brocade drapes of a four-poster bed seem of superior craft to those of their contemporary cultures in Renaissance Europe. A plate rack bearing a striking symbol of a tiger on a dragon, when hung upside down reads as Arabic writing, an illusion in which the animals are no longer discernible.

Katia and I have witnessed a classic confrontation: a modern Algerian man in business suit driving a new Volvo station wagon rear-ended a two-cylinder Citroën of a traditionally robed, turbaned, bearded man. The traditional figure is furiously shouting and gesticulating. The westernized Algerian is calm. The traditional man claps and waves his hands violently. I prefer the Minnesota way, a shrug of the shoulders, an exchange of business cards, phone numbers, and insurance policy information, each leaving quietly and apologetically.

School children are everywhere in Algiers, including outside our hotel window each morning. They are the same as kids everywhere: hyperactive, teasing, and enthusiastic. The elementary curriculum is in French rather than Arabic or Berber. English is usually the second language taken up in secondary schools. Among a group of school kids on recess are two, perhaps nine years old, who have gotten into a brawl and are going at it. Their friends gather around in a circle to encourage them to fight, which they do, mainly wrestling but with kicking and kneeing, and now, suddenly, full-bore slugging. The sweaty redhead is head to head against the curly dark head. They become serious about it now and their colleagues finally try to separate them as tempers are out of hand.

Katia and I dined last evening in a restaurant with our host, around a low round table on which we were served a traditional country meal. It began with a savory soup of vegetables, bits of meat, pecans, peppers, tomatoes, and lemon, served with pan bread. The bread had sesame seeds throughout, plus a lovely crust, and a light, coarse-textured interior. The main course was Couscous, the basic ingredient of which is semoule., pre-prepared in round, heavy wooden platters by adding water to flour and rolling it over a large surface, then running the paste through filters of different sizes to arrive at different coarsenesses of grain. It is then steam-cooked twice to achieve the proper size and consistency. Many varieties of ingredients are mixed with the basic grain: raisins, dates, seafood or chicken, lamb, or sausage. The whole is covered with a soupy vegetable sauce that one mixes to taste using chili peppers and seasonings.

Off to the Sahara

Tuesday, February 15, 4 a.m.

The stars are out, the monsoon has ceased, and we are en route to Ghardaia in the northern Sahara. We are told it will be very hot during the day and very cold, perhaps with frost, in the night. At the airport, we are seated next to three elegant ladies in their late 20s or early 30s, dressed traditionally but in chic long robes, one in olive and two in deep blue. They wear handsome, dainty lace veils that jet out stiffly following the line of the nose. Two wear elegant pointed shoes and one lovely leather boots and are obviously members of a wealthy traditional Muslim family. Though their faces are masked, the eyes are bold and curious. They inspect Katia and me, scrutinizing our clothes, our faces, our demeanor, trying, we suspect, to divine our relationship. Across the way is a group of five Algerians, three men and two women, one toting a Farfisa keyboard, en route to some desert resort to provide Western-style pop entertainment for tourists. The clash here between the old and the new world is amusing , but one senses it is not a happy one.

Ghardaia and the M’zab Oasis

The city of Ghardaia is pyramidal in shape and strangely luminous in the early reflected light of dawn. As the sun emerges, so do the colors; ocher, beige, and light blue dominating. Three mosque towers are visible as well as a remarkable obelisk at the summit of the town. We are quite ignorant of what we are seeing and eagerly await our guide. From our hotel balcony, Katia and I watch the sunrise, enchanted by the morning scenes of this ancient community in the middle of the Sahara, an oasis in a shallow valley with walls 120 feet high. The several townships of the M’zab Oasis extend into the distance, each on distinct conical prominences. The five original townships of the ancient M’zab oasis, now under one government, are Ghardaia, Melika, Beni-Isguen, Bounoura, and El Attuf; making up a community that approaches its millennial anniversary.

Scenes in the Sahara

Ghardaia overview

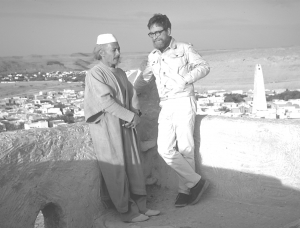

Our Beni-Isguen clerical guide, Moussa (Moses)

Ghardaia Scenes

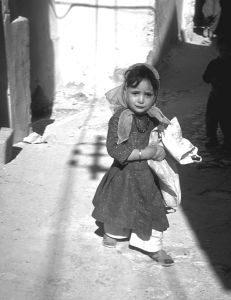

Little people of the Sahara

The Police

Our flight from Algiers at 5:30 a.m., on a Boeing 737, was completely filled, as apparently are the four flights daily to and from this desert community of 100,000. Just as our craft was about to depart the gate, I was abruptly summoned by a steward to the rear of the aircraft: “Please come speak to a gentleman who is anxious to talk to you.” The “gentleman” in a khaki jacket was unprepossessing, with a stubble of beard and an undistinguished face. He identified himself as from the Algerian Police and asked who I was, where I was going, what I was doing in the country, and was I a journalist? It dawned on me that he may have been tipped off by police in the airport as I walked about dictating the earlier scene, describing the contrasts in cultures and faces waiting for departure. Whether journalists are allowed to voyage unrestricted, I don’t know. Certainly the young embassy couple on the plane with us had to go to considerable lengths to get permission to leave the city of Algiers. They spoke of an impression here that “the American government is trying to overthrow Algeria,” and with it a general civil hostility.

At any rate, in my interview with the policeman, I was grateful for my capacity to speak French. Otherwise, we would have certainly been removed from the plane and our papers examined in greater detail. Fortunately, I also had a copy of the hospital conference program bearing my name and a business card from our host, Dr. Feghoul, which I produced from my pocket. The policeman was quickly satisfied of our legitimacy and allowed us and the plane to depart.

It is ever so chilling to come face-to-face with the police state. {On 9/11, of course, we regretted not having been more careful about our own visitors to the U.S.!]

Our Ghardaia hotel, “Rostemide,” is low-lying against the bluff, in adobe, fitting perfectly into the surroundings. It is a resort hotel, probably the best one within hundreds of miles, and a number of French-speaking tourists are guests. The lobby is decorated with Algerian rugs and tapestries, magnificent weavings in primitive, Indian-like designs; others looking Oriental but not at all like Middle Eastern rugs. The smaller ones, 2 x 5 feet, are for sale in the range of 600-1200 dinars, the ones at 4 x 6 feet cost 2000-3000 dinars or $600-800.

It is an hour past our rendezvous time with the local pharmacist. I was assured on telephoning his office that he was on the way. The young French couple said to us, “Don’t be in a hurry here. This is, after all, a charm of the Orient, the failure to recognize time.” As we watch the sun rise over this peaceful scene we understand that time is indeed different here, as is personal identification with time and with the past, in a continuum in which an hour or a day or a week has little importance in the grand scheme. Time urgency is a distinctly Western malady.

Excursion into the M’zab Oasis

Katia and I came into the capable hands of M. Bassa Salah, the local pharmacist, who immediately took us outside the city into the ancient oasis where it is fresh and cool in the shade of date palms. Extensive construction goes on as families divide and subdivide inherited land and build little gardens and houses, expanding from the old center of Ghardaia. The wall construction now, instead of adobe, is either of stone or concrete blocks, easier and stronger and less liable to fall in a flood, but so little attractive.

We see all nature of produce growing under the palms: carrots, herbs, apricots, and oranges, all watered by ancient aqueducts running throughout the oasis. Hard-working men return home at siesta time and work a couple of extra hours a day on their own homes and watering systems, fantasias with spiral columns and eastern arches copying Middle East Arabic architecture rather than their own traditions. Mr. Salah, our host for these two days, led us deep into the oasis where we feel privileged, with a certain reverence, on entering this ancient, quiet, Muslim community.

M’zab Oasis Scenes

Katia with irrigation expert of the oasis

We learned from our guide about the partitioning of the water supply and the ancient water-watch towers, still manned 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, to detect the “coming of the waters,” that is, flash floods that funnel into the narrow gorge at the oasis of M’zab. When the floodwaters are seen arriving, guns are fired and people climb on the wall to celebrate. Those who do not want to get caught in the oasis for the several days of flood, quickly make their exodus. The waters enter the ravine and, depending upon the amount, water is partitioned in three directions toward parts of a large area that extends into downtown Ghardaia.

Two gentlemen, heads wrapped in loose cloths, pass by on donkeys, carrying palm logs home as fuel. Donkey droppings, goat droppings, and human droppings are used to fertilize the oasis gardens. A beautiful tree is full of bright lemons the color of oranges but the shape of lemons.

We penetrate the oasis from the hot exterior walls to the cool interior. Here the traditional wells are sealed, their wood hoists rotting away, though the ancient aqueducts leading from them are maintained serviceable, powered by many pump houses at the site of the old wells to boost water throughout the irrigated area.

When the waters arrive seasonally they flood down the main streets and engage carefully calculated openings in the street walls that divert water into channels toward the various gardens. The farther from the origins at the wall of the oasis, the wider the intake mouths.

“Dallas!”

In this ancient, silent place we note new metal electric power poles and lines and neon streetlights. Rural electrification has just arrived. Pump motors and television sets are disharmonious to the primitive calm.

Katia and my biggest shock of the whole oasis experience came as we approached the adobe walls of a dwelling. We heard from within the familiar theme song of the TV drama, “Dallas,” invading the serene and traditional scene. We were told by our guide that the local women are much taken with the story, interpreting it literally as American life. We feel Ugly Americans.

The fig trees have lost their leaves in February as have the apricots. But despite the absence of leaves there are early spring blossoms. The young keeper of the waters has just turned on an irrigation valve and a generator. I photograph him with Katia and then on his donkey, making rounds of the pumping stations to divide the water appropriately around his family property.

We are comfortable in the sun of high noon with light so pervasive that everything flattens; shadows are straight up and down at this latitude near the equator. The reverberation of light throughout this sun bowl is overwhelming, yet in shade the air is cool, almost uncomfortably so. Apparently, things are quite different in summertime when it hangs around 40 degrees C. and only gets a few degrees cooler during the night. Our host has lost his traditions and lives comfortably year round in his centrally heated and air-conditioned villa in Ghardaia.

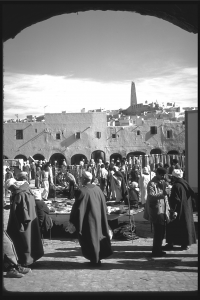

We caught a glimpse of the central market in passing, filled entirely with men in the early morning. There we spied an auctioneer selling off a used refrigerator and stove and an old sofa. In the background were brass and silver incense burners, probably copies of antiques but nevertheless imposing.

Lunch with a modern couple

Katia and I had lunch with a charming young surgeon and his wife, Dr. and Mrs. Hadjadj, arranged for us by our host the pharmacist, M. Bassa Salah. It was a lovely event in which they put on the royal treatment including Couscous Royale. We sat around a low brass table and started the meal with a petit lait, or buttermilk, and dates. Naturally, I had orange juice instead of the clabber. We moved to the table for the formal couscous with vegetables and local truffles and dried tripe with lamb chunks and a savory soupy vegetable sauce. Following an elegant eggplant and olive salad with a touch of garlic, we retired from the European table and returned to the low Arabian table where we were served cakes and mint tea.

Pleasant conversation centered on local customs, the deterioration of traditionalism, the work of the pharmacist in the National Red Cross and of the surgeon in general surgery. Both devote their lives to their homeland rather than moving to greater opportunity in the big city. The older man, the pharmacist, is a typical liberal of my generation, pleased to be involved in the recent revolutionary period against the French and to hold a position in the Red Cross. The young surgeon is among the professional and intellectual leaders of the community. He and his wife come from a town 40 miles away and he is one of only two general surgeons here. To his load has been added recently the departure on vacation of the only obstetrician-gynecologist; our friend must also take care of complicated deliveries. We discussed his work, which is typically trauma and general abdominal surgery, and a few special diseases prevalent here, including urinary stone, bladder stone in children, and echinococcal cysts of the liver.

We got into women’s rights. The surgeon’s lovely wife enjoys her three afternoons a week of life external to the home directing a beauty shop, for the creativity and freedom it gives her. She encourages this among other women and indicates that her young surgeon husband is supportive. The older pharmacist, however, expressed doubts about whether women should go in this direction. The older man decried the deteriorating personal values and mores, which he blames on television and a general “permissiveness.”

It is indeed as shocking here as it is anywhere, the effect of television on women who have never been outside their towns or seen behaviors outside their own families. Exposed in such traditional settings to the junk that is French, Algerian, and American television, what will transpire? It may be hoped that they interpret “Dallas” as a fairy tale rather than an exaggerated reality of life in America.

M. Bassa is not only a social leader in his community but a strong defender of it. The only near faux pas of the day (that we were aware of) was my mention of the work of Pastor André Trocmé in Algeria right after the liberation, when my former father-in-law set up engineering schools for diesel tractor maintenance. The pharmacist’s only acknowledgement of my story was to remark grumpily that often “the French told us that if they left we would be unable to manage things and our country would fall apart. We managed, perhaps a little slowly, but we managed to take care of the technical details of running our society.” Obviously, he is skeptical of even such enlightened missionary efforts.

With an almost overwhelming graciousness that we have come to accept without embarrassment, the doctor’s wife disappeared for a moment as we were about to leave. She returned with a lovely wall hanging about 18 inches by 5 feet in dimensions. In beautiful colors, it had been commissioned from a village woman and contained local symbolism about family life, the marriage bed, and household artifacts, as well as a few animal symbols such as the scorpion. I expect that Katia and I will wrestle with our conscience as to who gets to keep it.

Dr. Hadjadj took us to a vista over the entire valley and pentapolis. The whole is a huge oasis in the midst of the starkest desert. He maintains that historically the M’zab could not be recognized if one were as close as a half mile from it, without knowing precisely the coordinates or how to get there. Thus, it was an ideal refuge from the invasions and wars of the various Islamic sects between 600 and 1000 A.D. The Mozabites, the tribe that founded this valley and the five cities, later split according to their religious affiliation to establish independent communities. We talked about the region as a melting pot.

Ghardaia is, in fact, at an ancient crossroads of north, east, south and west caravan trails and it remains a major station on those routes though it is no longer self-supporting with commerce, agriculture or natural resources. The King of Morocco has apparently included Ghardaia in his territorial claims against Algeria, presumably because it is not far from major natural gas reserves.

The many different peoples represented here have remarkably different stature, facies, and complexions. They are Berber or Arabic or Black, but all are Moslems. The substantial numbers of dark skins, according to our hosts, are completely equal in every economic and social sense. Those we have seen have Hamitic, not Negroid features.

Beni-Isguen

The magnificent town of Beni-Isguen is the oldest and more traditional of all the M’zab communities, and until very recent times was closed to all outsiders, even, it is claimed, to the French colonial officials. It looks shimmering and almost plastisch in the light of dawn as will be suggested in my photographs taken from the ramparts. But it is equally exciting and harmonious in the full light of afternoon.

As we view the entire M’zab Valley, just below us on the left is a mosque with outlying temples and cemetery. Women in flowing white robes walk among the grave sites. The custom is that bodies are bathed, wrapped in good cloth and buried about 3 feet deep and without formal grave markers, only a stone indicator.

Down the hillside, we enter the ancient city gates, the eye of the camel, “just high enough for a man on camelback,” (and, according to The Bible, just narrow enough for a camel with a poor man on his back.) Climbing the streets of the village we soon met our guide, Moussa, which is Arabic for Moses, a handsome man of dignified features, dressed in a simple robe and turban. He kept us entranced through the afternoon and early evening describing the architecture and culture of his village. Not only were the main portals throughout the community just camel height, but the streets were carefully calculated in width and height for the houses to meet several basic criteria: intimacy of the family, privacy, and the rights of neighbors. The height of houses is calculated with respect to width of the streets so that no house would completely block the sunlight from another and so that no entrance to any house would be directly across from the entrance of another. Doorways are staggered all down the street.

In all houses there are two doors, one to the visitors’ quarters and one to the family’s. Above the doorways is a tiny opening at the top of the arch from which people on the second floor can identify the visitor. There was, of course, no idea that we could enter any of these doorways, but our guide took us far enough into alcoves to see the ancient wooden posts that serve as hinges and to note the wooden keyholes and keys.

The streets mount at an angle and with steps of 2 to 3 inches, appropriate to the gait of camels, though camels are no longer used. The streets are planned, moreover, to provide maximal light but also shield from sandstorms. At every turning is a communal well divided into two sections, one for women and one for men, so that they are not forced to communicate when they come for water. The well doors were opened for us to look at the old wheels and the well-worn crossbeams, which are no longer in use, there being mechanical pumps for each of the wells to supply households in their close vicinity.

Only women and children were in evidence in the streets of the village, the children playing as children do everywhere, and the women chatting at corners and in the entryways of houses as they do in most warm countries. We passed the mosque where wedding ceremonies were described. Again, they are segregated, men on one side, women on another, never to communicate. We passed the Koranic School, attended by all children for part of the day for religious instruction, and we met a number of the young religious instructors wearing white embroidered caps.

We finally reached the square at the summit of the conical city and the defensive tower called “The Tower Built In A Night,” the top of which is made of plaster rather than stone because it was indeed built in one night, during the urgency of a 14th century invasion. We climbed the well-worn stairs and saw the slits in the ramparts for firing rifles at an angle. From the top I took numerous photos at sunset of our host, Dr. Hadjadj, and of our guide, Moussa, including magnificent scenes, I hope, of the walls and buildings of the city falling away below us in the evening sunlight.

All the way down to the lower main square, our guide Moussa served as protector of the morals and traditions of the community, making critical comments to children playing too loudly or vigorously and to tourists, particularly three ladies he scolded for being in this part of the town close to prayer time and without an official guide. Indeed, with complete authority, he turned them back down the street. All his admonitions seemed to be followed respectfully by all the children he accosted. He is obviously either revered or feared by the community. [We Americans were to learn much more about the moral and political authority of Muslim clerics from our adventures in Iran, Afghanistan, and Iraq!] The moral object of the billowy clothing, other than its practical value for the climate, is that the human form, whether male or female, should not be discernible. This is apparently a crucial part of Islamic code.

Mass Masculinity

Finally, we arrived at the main square, an overwhelming experience of mass maleness. Our companions and the men of the square greeted each other warmly in the Mediterranean fashion, shaking hands, linking arms, embracing and smiling, with many particular greetings directed to our guide, Moussa, and to our host, the surgeon, both widely known throughout the oasis communities.

We learned here that women have the right of congregation in the rest of the village, where men cannot loiter, while in this commercial square women are not allowed to tarry, having only rights of crossing. All men of the town were present, standing or seated on rugs around the bazaar, listening to hucksters and auctioneers presenting a large armoire but not making the sale. Other salesmen displayed coarse muslin cloth, calling out its price, also not selling. While around the periphery of the square were dozens of shops, each small, cluttered, cozy, and highly specialized, for example, in dairy products, or vegetables, meats, notions, rugs, or souvenirs. The local produce included measly tomatoes, handsome huge carrots and radishes, good-looking navel seedless oranges, dates on stems, and many seeds and nuts and fruits.

Our guide, Moussa, continued to scold and moralize all along the way, expressing his loudest criticism of some anonymous person who had perched a small child in a niche about five feet above the street and abandoned her there. I suspect she had requested to be put there. At any rate, he made no effort to remove her, only sermonizing about who had committed such an irresponsible act while admonishing others to rescue the little one.

Hour of Prayer

There seemed suddenly to arise in the main marketplace an excitement, an increase in the pitch of sales, a scurrying to and fro. This was because prayer time was due in a few minutes, at which moment all commerce would cease and all tourists and visitors must be gone from the old city. We hurried to buy postcards and to take a few snapshots, being careful not to take people face on or to photograph women, rather to concentrate on buildings, vistas, and on children.

Most Mozabite women are completely veiled except for one eye peering through a tiny opening. Others are veiled from the nose down with only eyes visible. Our traditional colleagues remarked on our comments that the eyes seem rather handsome and cosmetically made up, including carefully plucked eyebrows. He said, “Yes, true, but that is not the purpose of the veil, to enhance or to display beauty, but rather to cover it. A married woman must not be seen by anyone who is potentially marriageable, including first cousins. The younger mature girls were also covered and partially veiled but most of their face was open. The only adult women not veiled according to our host were a few unmarried women and foreigners. Even the relatively “liberated” wife of our medical host, who spends three afternoons a week in her beauty salon and who dresses in western fashion in her home, and who is enthusiastic about women’s professional satisfactions and rights, apparently also respects the traditional pressures. She goes completely veiled when outside the home. It was hard for us to conceive of this open, smiling, educated, intelligent lady walking about the streets in bourka and veil, but such is the case.

After our morning in the oasis, a magnificent lunch, and the afternoon in Beni-Isguen, we returned to the hotel exhausted and fell soundly asleep, regretting that we were to be met again for an evening engagement. Our host for the evening, Dr. Doudou, a local ophthalmologist, arrived promptly at 9 pm. A good-looking man, partially bald, in his early 40s, he was dressed in a handsome dark blue wool cape made by his wife. His plan was to take us “to view a little of the interior,” in contrast to the exterior that we had seen during the day, by taking tea at his house. There was no way I could gracefully refuse, so I went upstairs, woke Katia and off we went to his newly built house on the outskirts of Beni-Isguen.

The doctor’s new house was built in the local style. It was obvious that in the outskirts of the expanding town the sewers were not in order. Fortunately this was not evident inside the house, which was far more traditional and more elegant in the style of country than the home of our luncheon companions. We entered a charming salon with the bright colors of pillows decorated in ocher and gold and brown by the 18-year-old daughter. Katia heard but I missed somehow that the wife would not join us, not allowed to present herself to other men. Meanwhile, I kept waiting through the long evening for her to appear. She never did.

In another room she prepared an elegant silver tray with tea and four glasses for the three of us, the fourth symbolic of her presence. Pastry was baklava, heavy in honey, fat, and chopped nuts, and on the tray were fresh almonds and raisins, pound cake and prunes, and navel oranges. We had learned that it is customary to take three servings of tea, which, in addition to slaking one’s desire for tea, provides a finite, appropriate duration to any usual social intercourse.

Our conversation ranged widely, about his family of two boys and two girls and of how he and his wife and a few colleagues, concerned with the disappearance of local artisanal crafts, organized a school for cloth crafts, embroidery, weaving, dyeing, in which his older daughter is leader and teacher. All the lovely pillow cushions around the salon were made by this daughter. Though we admired them greatly, I tried not to rave too much for fear the cases might be removed and given us as gifts.

Katia and I were particularly interested in our host, Dr. Doudou, because he was among the more sophisticated and thoughtful and articulate of our wonderful M’zab hosts, all of whom had those qualities, but, at the same time, he was the most traditional and religious. He talked to us a great deal about Islam and decried the violence of the Islamist sects that assassinated Sadat in Egypt and have murdered thousands in Iran in recent times, pointing out the basic non-violence of all religious tenets and codes. He described the strong role of Islam throughout the centuries and particularly during the French colonial period. It provided a democratic, republican forum and a union that the French could never penetrate, either with their bureaucracy or with their Catholic missions, which he claimed converted “not a single soul in Ghardaia!”

The “democratic” [his term] Islamic tribunes controlled many social and civic functions over the years. Church and state are now united and Algeria is an Islamic State just as Iran, though Algeria has more democracy and tolerance of various religious unions. The whole, so far, is non-violent. [Sadly, Algeria is no longer non-violent but has been wracked by two decades of fundamentalist terror, on one hand, and military tyranny on the other.]

He spoke of the subtleness and suppleness and adaptability of Islam in its desire to move to a degree with the times, not to refute technology, and to support a literate, educated populace. I had not been aware that the French colonial government had allowed no Algerians in the university and had no strong public school system for them. Several of our hosts during the day spoke of the intellectual strength in the communities of the M’zab because of the Koranic schools maintained during the long French occupation and the even longer intellectual and academic tradition of people from this area.

Doudou spoke with optimism of Islam and the Islamic state being able to maintain unity and vigor along with technological and economic advancement. He recognized the tremendous power for good and evil, mainly evil, in television as it now exists. We talked for some time on the how and the why of the huge impact in Algeria and elsewhere in the world of TV series such as “Dallas,” for its shocking and distorted depiction of western living patterns and duplicity among the wealthy.

Algiers: February 18, 1983

Today Katia and I are back in Algiers City, spending a day touring with a young cardiologist, Dr. Mohand Said Issad and his father, Mohammed. Last night Katia danced with the young physician and I danced with his girlfriend, Minouka, at a delightful evening celebrating the closing of the Hypertension Symposium. He offered to take us on a tour of an unusual and different part of Algeria, the homeland of his Berber father. Though he promised a long and tiring trip, we have had nothing so far but great experiences by accepting invitations and letting people show us what they wanted to show us, not worrying about our own comfort. [Unfortunately, this side trip sadly tried our endurance and patience and broke the mold of warm hospitality for us. C’etait tout simplement trop!]

Excursion to Kabylie in the Atlas Forealps

We are perhaps 50 miles out of town in a not very attractive mountain village on their Sabbath (Friday), and the streets are full of men. Back and forth they walk, twirling their canes, looking dignified in their turbans and robes, going to market on errands or taking care of children. No woman is to be seen. What a strange man’s world. The woman simply is not here, she is at home.

Some Berbers have red kinky hair and some are surprisingly blonde but most are North African “looking.” We begin to understand differences between North Africans, Berbers, and Arabs. I’ve always considered Algerians Arabs; they are not. The Arabs and Turks have, however, invaded the region back and forth throughout history and this area is a major point where the advance of the Turkish Ottoman Empire was arrested. In fact, this very town is a steep natural pass and resistance was strong here. They claim that they are basically one peoples, that there was once a huge North African Empire, and that a strong North African feeling exists still. Actually conversation is ongoing in an attempt to create the equivalent of a European Economic Community of North African States. The main obstacle to that state, they claim, is the royalty of French Morocco, which is expansionist these days.

On the other hand, one can see much communication at the professional level and much affection between the groups. For example, our hosts today, Dr. Issad and his father, are Moroccans by adoption because they love the culture and the country and lived there for many years, the father being educated there. The Moroccans and Algerians and Tunisians were obviously “brothers” in our celebration last night, both in their professional and social intercourse.

While we are posed in this country town waiting for a tire to be repaired, I comment briefly on last night’s celebrations:

The closing conference ceremony was a banquet of the faculty and selected members of the symposium audience, held in the elegant ballroom of Algiers’s El Djazair Hotel. A magnificent table was spread with hors-oeuvres and cold meats of many varieties, fruits, and an excellent if slightly sweet, rosé wine. We stood around talking for so long that at meal time there was no more table space next to the Tunisians, Algerians, or Moroccans. Katia and I ended up sitting at table with two “Colons,” formerly military physicians in the colonial government of France, one from Lyons and one from Marseilles, Dr. Mailloux and Dr. André. They had much to tell us about the colonial period, told with obvious love of this country, where they still hold dual citizenship. They appear to have managed the transition and are accepted by the locals and still have important medical functions consulting to the Algerian military. Wouldn’t you know it, they were Protestant and, of course, knew well Katia’s forebears, the famed Famille Trocmé of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon!

We left their table, nevertheless, at the earliest opportunity and went toward the group of locals who were beginning the dance. The women dancing make very subtle hip motions along with a slight rotation of their hands, all understated, lovely and quite sensual. Our host Dr. Feghoul was particularly cordial all during the day’s conference and in the evening, and in an expansive mood, said that Algeria had “adopted” me. As the evening broke up we kissed on both cheeks. A marvelous “type,” he insisted on Katia dancing, which she proceeded to do for the rest of the evening, including with Dr. Issad, which accounts for our mountain trip today. I danced with Dr. Issad’s girlfriend and found it delightful. With a slight modification of my basic jitterbug it went very well with the native music and the six-piece orchestra.

Invitations of colleagues to Casablanca and Tunis were sincere and I’m sure we could develop them if we want. It seems that I have never thought seriously of North Africa as an interesting cultural or professional contact. In fact, it combines nicely my interest in warm, exotic lands with my French speaking and with anthropological and epidemiological issues in an area with rising rates of hypertension and coronary disease. There is a particular issue of the mineral composition of the various aquifers from which different communities, all of the same ethnic background, are exposed to different salinity and hardness of water. The relationship of water to health and vascular disease might very well be clarified here. It would be easy to sample levels of these aquifers, whereas this is a difficult problem in the U.S. because our water sources are so varied, even in one community.

[Though I never developed these possibilities for field work, a few years later we enthusiastically welcomed to Minnesota M. Claude Pacque, of Rabat, the grandfather of studies of blood pressure and salinity of the Moroccan aquifers. He turned out to be dysthymic and in his visit here was quite manic. He left us all mystified, dumbfounded. We never followed up on any of it.]

The Excursion to Kabylie Resumes

Well, after all, the tire wasn’t reparable; our host bought a new one and we started up the mountains through a magnificent green valley. Our conversation flitted over many subjects, the old gentleman being an expert in many fields of his native land. We are still confused as to what is Arab and what is Turk and what is Berber and what is Algerian and what is not. I’m sure things will fall together as we learn more. In this region, his home country, Kabylie, there is a Berber tradition and Berber language. Of course, everybody also speaks Arabic but it is still considered the “language of the invaders.” The local language and culture have always been different and independent, just as the desert Berbers are. They try to maintain a Berber feeling, and call Berbers “the native race” of North Africa.

The villages are all perched on mountains and promontories of the long mountain ridges. Just as the mountain villages of Italy, these too are failing. Apparently it is from this region that many of the Algerians come that are now working in Europe, their wives and families remain here in the salubrious mountain air while the men work and send money home.

Their indigenous culture is surely doomed. They can no longer subsist on the olives and grapes and the small amount of gardening and herding that is possible at altitude. They eat primarily imported beef rather than lamb, which doesn’t thrive at this altitude, and there is clearly not enough food for the burgeoning population. The villages are still more vital than the mountain villages of Italy, but there is no obvious way that they ever again can be self-supporting. [Another project for Bill Gates?]

A Social Shock

These two delightful gentlemen, the young cardiologist and his magistrate father, had given a whole day of their lives to take us to their special region. Because of the bad weather and the distance we did not stop in to see the grandmother en route but had spent seven long hours in the car. On our return, just as we were approaching the city, they sprung on Katia and me that the wife and mother had been at home all day preparing a special couscous for our dinner! They had mentioned it not at all last night or even this morning on picking us up. We had not had half an hour to ourselves in Algiers to think, to organize things, to pack for departure tomorrow, or to visit with one of our hosts, M. Bouier, now waiting for us alone in the hotel. It was suddenly too much!

All the good feelings of the day were spoiled when I declared that their proposed plan was awfully kind but was out of the question; they would have to excuse us to their good mother. We were exhausted. We needed time alone. We were leaving early on the morrow!

Katia and I felt that we had been patient, going with the flow everywhere invited. But this invitation proved too much for our state of fatigue. The cultures clashed. In one it is quite unacceptable to turn down a family meal invitation. In another it is quite unacceptable to surprise guests with such an important invitation at the end of a long work day and week, when we had other needs and plans for the evening before our departure. [You can tell I am still embarrassed to think of it!]

We continued, however, to chat civilly, where it turned out that the magistrate is quite “old school.” When I asked him about Algeria before the war, he said, “Well, here it was calm and delightful for the French colonials but not very comfortable for the rest of us.” He also opined that the revolution “has not realized itself.” He compared it to the Castro Revolution, in that land reform hasn’t succeeded, the farmers are paid just like any other laborers and, without incentive, produce poorly. And the people participate not at all in decisions under the military dictatorship. Addressing his son he said, “You will see, my son, when you have your socialism, nothing will work.”

Algeria today is not, of course, either socialist or democratic but is torn by vicious clashes among Islamists or fundamentalist terrorists, Muslim non-observers, and the clique around the heavily military dictatorship. It is sad to recall our hosts’ great hope for freedom in Algeria 20 years ago.