“It Isn’t Always Fun.” – The NAS/NRC Diet and Health Report, 1985-89

Diet and Health

Report of the Food and Nutrition Board,

National Research Council,

National Academy of Sciences, 1985-89

In the mid-1980s, it was probably Dewitt Goodman of the American Heart Association or Mike McGinnis of the Public Health Service who nominated me to the National Research Council Committee on Diet and Health. I recently had completed a term with Goodman on the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association, participating in its major public report of the 1980s, had worked with McGinnis on “1990 Health Goals for the Nation,” and also at the time was writing extensively about public health aspects of diet and nutrition. It was an interesting and prestigious appointment that I quickly accepted.

The new task proved, however, a major and burdensome responsibility. There was tedious committee work, correspondence, literature review, summaries and chapter drafts to prepare on a schedule that I could hardly influence. This all came down, moreover, during a period of my maximal commitment to the huge community research programs we had initiated in Minnesota, the Minnesota Heart Survey and the Minnesota Heart Health Program. I also had new and heavy administrative responsibilities and demanding academic issues as head of a reorganized Division of Epidemiology at Minnesota. On top of this, I was recently divorced and newly in love. All things considered, 1985 was a challenging and fun year.

I accepted the task primarily for the chance to learn more about larger issues of diet, health, and policy that had long been central to the research and thinking of our Minnesota institution. And at the beginning I was comfortable with my assignments: the first draft of a chapter on dietary fat and coronary disease and a chapter on criteria for the application of scientific evidence to national dietary recommendations.

The Committee functioned well at the outset, members having a great deal of respect for one another and seemingly for each other’s disciplines. The busy-work was ably administered by Sushma Palmer and Chris Howson, executives for the Academy, and by our co-chairpersons, Dewitt Goodman and Arnold Motulsky. Meetings usually were held at the National Academy on Constitution Avenue in Washington, an elegant building as distinguished as the organization it serves. During that period, the Academy was led nationally by Bryce Crawford, Professor of Chemistry from Minnesota, which provided an added cordial association for me. The Committee also met during a time when I was particularly active with a hobby, the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, which, on invitation, I brought twice to the Academy for concerts in its acoustically impeccable auditorium.

The years of meetings in preparation of our landmark report were rich and busy ones. Our correspondence got hot and heavy in mid-1987, when I produced a draft of Chapter 7 on diet fats that was heavily criticized by Goodman. It took some months for that situation to be reconciled, mainly because I was unable to understand or respond to vague feedback, for example: “This chapter needs to be brought up-to-date.”Rick Shekelle and Henry McGill translated our poor communications and filled in areas I had covered inadequately. I later fell behind with my assignments, mainly due to a six-month Sabbatical that involved extensive travels and responsibilities at the University of South Florida, Southern Africa, Finland, Norway, and Ireland. By then I had got in over my head both on the report and in my job at home. On top of all this, my relationship with Stacy was in full flower. I was overwhelmed and near drowning, with little possibility of being saved.

I made something of a brief comeback in a summarizing role for the major Academy diet-health conference of 1987 at the St. James Hotel in Washington, D.C., where I presented criteria to assess the evidence for national dietary guidelines. I pushed vigorously for dietary guidelines and nutritional goals designed both for populations and for the individual, addressing the separate strategies needed for their effective implementation. The problem is that such recommendations are most needed under the condition of uncertainty in the evidence, which is the usual case for diet-lifestyle-disease issues. Academicians, to the contrary, are inclined to think that recommendations for the public should be made only when evidence is firm and complete. They often speak (naively, I believe) of first requiring “proof.” Our task was, I felt, to translate the weight of evidence on dietary effects to the appropriate public health recommendations based on the best current evidence, while acknowledging that the evidence would never be complete.

Mark Hegsted, as a consultant to our group, reviewed our process and criteria before the Committee. He was widely known for his superb early dietary experimental researches and for participation in the Senate Select Subcommittee’s famous reports on diet of a decade earlier. While at USDA, he also had put in place a joint Department of Health, Education and Welfare-United States Department of Agriculture task force that developed the first edition of the U.S. Dietary Guidelines in 1980, which still exist with modifications. At our conference he cautioned, with great prescience, that the “scientific appropriateness of recommendations may be discordant with the feasibility or acceptability or topicality of such recommendations in any given period.”

It was the political undertakings of the Senate Subcommittee under Senator George McGovern that had provided the first real impetus to useful national dietary guidelines. Hegsted was one of the few national leaders in nutrition who understood and promulgated a public health strategy of dietary recommendations. Moreover, he was one of the few able to parry effectively the heavy attacks by the nutrition establishment on these views. His opinion was forceful:

Failure to address the public health issues is an abnegation of medical responsibility.

The Nutrition Old Guard Returns

At that point, we as a subcommittee had our final confrontation with our predecessors in the Old Guard of the National Research Council, those who had produced the Academy’s controversial, industry-oriented, do-nothing 1979 report, Nutrition and Health. We heard them once again voice the same old saws, along the lines of:

“One cannot define a typical U.S. diet any more than one can define a typical U.S. citizen.”

“We cannot establish that a change in diet leads to a change in disease rates.”

They quoted a notoriously biased authority of the times: “American Medical Association nutrition and health recommendations indicate there is a lack of scientific agreement.”

That infamous NRC report concluded with a plea for “moderation” in serving size, for the avoidance of no particular foods, and for focus of national dietary recommendations on excess body weight, not diet composition. That report amounted to a big zero for effective public health policy and action on the national diet, and was presumably exactly what agri-business sought. That earlier report also was intended as a direct refutation of McGovern’s Senate special subcommittee report. In our meeting with the NRC Old Guard, Lot Page, a distinguished investigator on our panel, challenged the old liners’ exclusively medical approach and diet recommendations directed only to those at special risk. He argued that individuals at risk cannot be identified precisely and therefore cannot be targeted.

Mark Hegsted closed our joint session with his powerful rebuke of the laissez-faire philosophy of prior NRC reports, that the individual approach alone to dietary recommendations is “an abnegation of medical responsibility.” Then he highlighted the main conceptual source of the controversy, that is, the individual versus the population view of diet and disease. He suggested that we might find a compromise in setting “minimal goals and optimal values” for both individuals and populations.

Seeking reconciliation with the Old Guard, our co-chair, Dewitt Goodman, emphasized that these two views, the medical or individual and the public health or population view, need not, and should not, be in conflict: “both approaches are valid, both are needed.”

[Of course.]

The conservative argument about diet has always been to require “high certainty of the evidence before making public recommendations.” The contrary public health view is that there would be little reason to deliberate and recommend at all if the available information were certain. In fact, it is the very condition of uncertainty in which public recommendations are particularly needed. But Hegsted suggested that recommendations might profitably begin in areas where agreement of opinion can be found.

Mike McGinnis, Assistant Secretary for Health for many years, who was a driving force responsible for the original Dietary Guidelines for Americans, emphasized four criteria for national dietary recommendations: They should:

1. Be faithful to the science.

2. Be consistent with other government policy.

3. Have utility to the public as their prime criteria.

4. Have a burden of proof that rests on those dealing with new evidence or new evaluation of old evidence.

We also discussed our panel’s John Baillar and his cautious criteria for public dietary guidelines:

1. Adequacy of the evidence

2. Acceptability of the risk

3. Benefit of the change

4. Existence of misinformation

5. Universality of the recommendations

6. Consistency with other recommendations

Internecine differences

Several of us sharply challenged the view of our co-chairman, Arnold Motulsky, that it is “impossible to make a single diet recommendation for a population.” We held to the contrary that it would be a dereliction if we failed to recommend a single average value [of a nutrient] as a population target and then elaborated on expected individual variations around that population value. He never budged.

Baillar pleaded throughout for a relationship of recommendations to the strength of the evidence. He indicated that he would be happy if we ended up simply with a better way of thinking about scientific evidence and public policy, whether or not we came up with a quantitative way of reaching conclusions. I found a guiding principle in his suggestion: to relate the intrusiveness of an intervention to the risk or the need, and to the nature and quality of the evidence.

Jim Dwyer, as consultant to the Committee, pointed out how the evidence is more supportable if we deal with dietary patterns of foods rather than individual nutrients. Michael Jacobson of the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) proposed that we focus on the best diet based on the science, without regard for acceptability, maintaining that it was the business of science to evaluate the evidence and not its acceptability by the public. He felt strongly that we were not charged with the socioeconomic implications of our recommendations.

Richard Peto, from Oxford, emphasized that the usual hierarchy of evidence, that is, from randomized trials at the top, then individual correlations, and finally international population (ecologic) associations, was, in his view, just the reverse of the reality required for public health recommendations. In fact, he showed that relationships of diet to disease rates are strongest among populations, where he used the Seven Countries Study as the model. Prospective individual correlations within cultures were next, while the least relevant, he felt, were those from randomized clinical trials among small, highly select, high-risk segments of the population. He also said that population observations are the most effective evidence of relative safety of diets. The burden of proof, he said, was upon those who say that dietary recommendations would not be helpful. [Peto’s points and pleas have since been borne out. He articulated effectively, in Oxfordian English, the message I had been fumbling to express editorially for years. But his sometimes sulfurous bluntness tended to tarnish his sterling thought and language.]

Conclusion-Confusion

In the fall of 1987, the National Cholesterol Education Program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) was getting under way and Dewitt Goodman was chairman of that undertaking as well as of our Committee. By that time I found myself in deep correspondence with a few members and advisors to the Committee who were, with me, pointing out major issues not being adequately addressed by Committee leaders or by individual chapter writers. For example, Baillar and I had prepared and circulated guidelines for making public recommendations in a draft of Chapter 4, yet apparently few in charge of chapter writing or final recommendations read or used them in their sections, supposedly our own Committee’s best effort at such guidelines. I also expressed concern, at that late stage of deliberations, that we continued to hold huge meetings and ponderous reviews of all Committee writings rather than using small work groups to focus on problem issues. It was the same issue of excessive democracy I had experienced with MRFIT governance and was apparently “required” by Academy policy. Again, these views lost out.

Goals for the Population. The Going Gets Tough

As late as December 1987, I wrote to colleagues: “I am a little pained but not yet distressed by the continued evidence in our discussions and in the minutes of meetings that some of the leadership may not recognize the need and role of dietary recommendations or goals for the general population.” I went on to propose once again that we separate advice to individuals from public health recommendations.

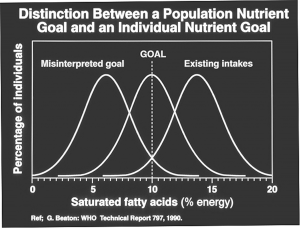

My model for such recommendations predated the better model George Beaton later produced for the World Health Organization (see figure below). Yet, in the subsequent minutes of our last meeting, I was dumbfounded to read, “there was a consensus that we limit ourselves to recommendations for individuals.” Seriously put off, I wrote colleagues: “In my view, we still have a long way to go to provide recommendations that are credible and useful to the general public; this from the leading independent scientific agency of the country!”

I also began to plead earnestly that our report would be incomplete and outdated if it contained only a presumably intelligent narrative review that failed to use summary statistical approaches available to us or to carry out needed new ones in a few areas. I suggested most strongly that our statements on total fat intake and several types of cancer would not be up-to-date without such a meta-analysis. And I proposed that Tom Louis at Minnesota, who had agreed to help, might be drafted to carry it out.

I sent my critical and increasingly insistent advice addressed privately to Chris Howson, project director, and to Sushma Palmer, director of the Food and Nutrition Board, rather than to the Committee leadership, because now I was getting pretty specific in my criticism. These staff, naturally enough, catered to the leadership rather than to the protestors. In response, I was given more work to do. For example, I was commissioned in February 1988, already very late, to write a new chapter on potential beneficial and adverse effects, including estimates of risk reduction if the public actually followed our guidelines.

The individual goal for saturated fatty acid intake may reasonably be an intake of less than 10% calories. But the population goal is to bring the [then] current mean of 14% calories to 10%, recognizing the distribution around that mean. (From George Beaton: WHO Technical Report 797, 1990)

In a very late memo, written October 5, 1988, I vigorously criticized the Obesity section, primarily because of its confusion, in my view, of individual and population issues of obesity and its lack of recommendations at the public health level. I complained further about an increasingly anti-red meat stand in the summary rather than leading with a positive statement such as, “fish and skinless poultry and specified cuts and grades of beef and pork can provide excellent sources of protein with lower accompanying fat.” In support of this view, I enclosed a letter from Nancy Ernst at NHLBI, who indicated how a public message focused mainly on decreased saturated fatty acids might result in a desirable decrease in total fat intake but, in fact, could increase intake of unsaturates and vegetable oils. [And that is exactly what has happened.] Little of my late-arriving critique was adopted. I suspect that by then my criticisms were perceived as negative and were most likely annoying.

Finally, in December of 1988, much too late to do any good, I received a detailed critique of my draft chapter on fats from our always helpful but often tardy colleague, Jerry Stamler, which, if it had been received earlier would have been useful. It put greater emphasis on dietary cholesterol and on diet effects independent of blood lipid effects. But basically it came too late.

Then, quite late in the game, on January 23, 1989, I sent a private memo to Howson and Palmer conveying comments from John Potter about the cancer section of Chapter 7 on diet fats. He had said sharply: “In its present form, this document will surely attract major criticism for its neglect of a systematic critical appraisal of the literature, its lack of proper weighting of different kinds of evidence, its inconsistent organization and presentation, and its lack of biologic and epidemiologic integration.” Zowie!

These strong comments were on the mark and highly appropriate to much of our academic, non-public-health oriented report. But I should not have put my signature to such a blistering critique at such a late stage. Potter’s comments, and my accompanying memo, brought nothing except ill will. The cancer chapter was already writ in stone. I simply should have resigned.

At the very end, in March 1989, I received with others a warmly expressed “form” letter from the project administrators. That spring, a public meeting was held at the Academy with presentations of our data in fancified, multicolored slides. By that time, much of the wind had been taken out of our sails by the preemptive publication of the Surgeon General’s Diet and Health Report, produced by an entirely different team and strategy, but which, nevertheless, came up with similar recommendations to ours. Our report was regarded in reviews of it at the time as a “scholarly and balanced report,” but the Surgeon General’s report received more public attention and acclaim. It still does, these many years later.

The immense effort of so many for several years on the NRC Diet and Health Report was, quite simply, not worth it.

This holds lessons all academics should heed before signing on to years-long service to produce a canonical report — by any agency — in any field.

Follow-up

Yet another subcommittee of the National Research Council was immediately appointed to consider dissemination of the public report. Its charge created annoying new issues, while its convocation exaggerated old inter-personal frictions that Committee members had developed over time. Its meetings were an unpleasant anti-climax in which, I suppose, fatigue with the whole procedure had accentuated everyone’s irritability. I was glad for that job to be over and to turn my attention to the renewal applications of our major Minnesota Heart Survey and Minnesota Heart Health Program grants at home, and to prepare for stepping down as Division Head in 1990.

My final ordeal of Diet and Health was in this public report subcommittee, dealing with its Academy editor who used throughout the popular journalistic pitch to individual readers in terms such as, “your diet; your risk for chronic illness.” After I had spent three years trying to get a public health view into the National Academy report, it was now to read like any newspaper health advice column, addressed to individuals and their personal dietary concerns and neuroses. [Zut alors!]

Finally, I protested strongly: “At least in the subtitle, and certainly in the content, should we not bring forward the family need, the social need, the community need, and the public need for changed eating patterns? Otherwise, we have done no more than advance another dime-a-dozen book on ‘your health and your diet.’ Literally hundreds of such books exist. Moreover, we are offering individuals an extremely attractive new way of life, not a sacrifice of pleasures as the tone now implies. Why not emphasize the ethnic eating patterns that have been tested by centuries of great eating, rather than grinding out low-fat modifications of the All-American staples: low-fat macaroni and cheese casseroles, chili, and hamburgers? I don’t think this is the message we are trying to convey.”

“Also, it just doesn’t make sense not to have these recommendations given in an orderly fashion as percent calories, absolute amounts, then a choice of foods, and finally, the desired eating pattern. And we simply must get away from the following kind of misleading statements: ‘every one percent reduction of your total serum cholesterol reduces your risk of coronary disease by two percent.’ That is simply not so. No way! Please, please take it out!” [Dammit]

This editorial exchange was so frustrating and infuriating that I’ve never dared look in the final published version to see what actually happened. I still don’t dare. Because I still care.

In our conclusion to the public report we also had to deal with the openly admitted bias of Chairman Motulsky, a geneticist, against any public health strategies and his expressed dream, which I quote precisely, that, “One day soon we will be able to identify high- and low-risk people and tell them what to do; we will then not have to bludgeon the whole population with diet advice.” [Double Dammit!]

Three years in discussion and he still hadn’t budged from his precious genes! My messages fell on deaf ears. In summary, they were, and still are:

• Eating patterns are socially learned and culturally determined.

• If the culture is unhealthy, no matter what our ability to identify individual risk, high or low, there will remain a need for approaches to family, friends, community, and the whole society to reduce the risk for each and all.

• A promise that we will ever be able to identify good and bad genes to the exclusion of concern about population-wide cultural effects and the incessant blandishments of industry to “Eat More!” — and thereby avoid the need for a more healthy eating pattern — is pretty much hot air.

• Humans are, after all, one species. And most members of modern human populations are susceptible to the current mass phenomena of atherosclerosis, elevated blood lipids, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and common cancers.

• The mass expression of susceptibility rests with the culture — not with the genes.

Sequel

I have remained good friends with Committee colleague Rick Shekelle, with whom I worked closely on the report, and I stay in pleasant contact with Henry McGill on a number of issues. Our chairman Dewitt Goodman has since died tragically from a perforated intestine with complications. Since those trying times, I have responded with enthusiasm to a solicitation from Sushma Palmer to write a short piece on population versus individual dietary recommendations, which was right up my alley. I continue occasional correspondence with some of the others. The geneticists still avoid the cultural issues in diet and health and we seem to mutually avoid one another. In semi-retirement, I dropped out of the national scene in nutrition following a “last hurrah” with the Dietary Advisory Committee of FDA and a New England Journal of Medicine editorial in 1996. In it I expressed profound concern about FDA approval of a mass experiment on America with Procter and Gamble’s fat substitute, Olestra (Olean ©).

What ever happened to Olestra?

Epilogue

I surely learned more than I contributed to the NAS/NRC Report on Diet and Health and am modestly satisfied with my efforts for Chapter 28 on criteria for public recommendations. The whole experience of the report might be compared to an attempted balloon voyage around the world: awfully difficult getting off the ground, a terribly cold and tumultuous excursion on high, a precipitous and bumpy landing, and then — oblivion.

* * *

Final Report

NRC, 1987