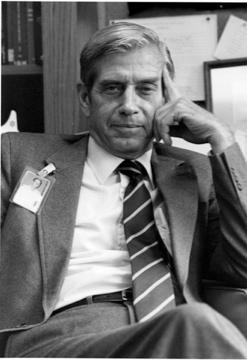

Reuel Arthur Stallones, MD, MPH

1923 — 1986

“Stony” Stallones was from Arkansas, son of an itinerant preacher, and acquired some of his skeptical attitude, folksy views, and direct ways from pioneer stock and simple origins. He completed his undergraduate education at the University of Michigan and in the accelerated Army medical training program Case-Western Medical School, and took an MPH at Berkeley, becoming an Army epidemiologist and MASH unit medic during the Korean conflict. He said it was a long time before he could see anything funny in Alan Alda’s long-running TV series. The best thing about service in Korea was his introduction to Japan, to which he would return often as a visiting scientist. After Army work on heat injury, respiratory outbreaks, and other health problems of recruits in training, he later turned to research in chronic disease epidemiology. This work emanated from Berkeley and covered the Pacific Basin where he studied the still unexplained cluster of Lou Gehrig’s disease in Guam, cardiovascular diseases in Samoa, and was central in setting up the migrant study of CVD in Japanese living on the mainland, in Hawaii, and in California (NIHONSAN).

Stony’s incisive criticism of epidemiological thought and study were among his finest contributions, always penetrating and original. His calls for a more progressive view of epidemiology are well illustrated by his 1980 article, “To advance epidemiology”, in which he argued for a new understanding of causal relationships: “An approach that holds promise is to consider the interdependence of a number of diseases, characteristics of individuals, and environmental and social variables as elements in a constellation which is n-dimensional, and within which directed pathways are incidental to the complex as a whole.” (1) In other words, Stallones meant that we should recognize the bias in our chosen beliefs about causal relationships, avoid investing them with any sense of absolute truth, and retain them only so long as they seem useful.

He was a dedicated iconoclast. His Houston colleague of many years, Alfred Knudsen, once presented Stony with a framed copy of a New Yorker cover illustration – a New England beach cottage with 17 seagulls aligned along the peak of the roof. One faced opposite all the others. Stony took an amused satisfaction from this acknowledgement. One of his later publications resulted from his pursuit of the idea that “what has come down must have gone up.” From this premise he sought a persuasive explanation of the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in the United States that began in the late 1960s. Finding no unifying explanation of the rise that preceded it, he concluded that conjectures about causes of the decline were too frail to withstand critical assessment. (2)

Stony’s mentoring of several generations of young public health scholars was probably the most enduring of his contributions. Something of his character and personality is illustrated in the comments of a close colleague, Dwayne Reed: “…he taught us how to be critical sons of bitches, which he himself was. This was another side of Stony that he’d be a dear and wonderful friend, but a critical son of a bitch at the same time, who could just reach into the core of what you just said show you how stupid it was. I never met anybody like him….I think that’s the whole aspect of his greatness; that he was a person who really thought about what we do, questioned what we do, and made what we do more fun, too.”

He loved life, simple food and drink, and engaging company. He inspired his colleagues and maintained their collegiality while effectively punching holes in their thinking. (HB/DL)

Sources

1. Stallones RA. To advance epidemiology. Annual Reviews of Public Health. 1980; 1: 69-82.

2. Stallones RA. The rise and fall of ischemic heart disease. Scientific American. 1980; 243: 53-59.