“It Isn’t Always Fun.” – The U.S.-Soviet Health Treaty

“The absent are always wrong.” Italo Svevo

In summer 1971, I sent a manuscript to Bernard Lown, Harvard clinician and electrophysiologist, soliciting his comments on a study of sudden death in heart attack patients in relation to the frequency and type of ectopic, or extra heart beats found on their standard electrocardiogram (ECG). Suketami Tominaga and I had worked for several years on relationships between the ECG and mortality among Coronary Drug Project participants. Our study showed an excess risk of coronary and sudden death related to certain complex characteristics of the ectopic beats. The deeper we delved into the matter, however, the less convinced we were that we could effectively separate with this simple test and by our analytical strategies, the excess risk due to the ectopic beats themselves from that due to other characteristics of the diseased heart. Our findings, nevertheless, fit Lown’s thesis of the time. And, in our view, he knew then, and perhaps even today knows more than anyone else about the relationship of ectopic activity to fatal arrhythmias in the electrically vulnerable heart. The following letter came in response:

Harvard University

School of Public Health

Department of Nutrition

August 17, 1971

Dear Henry:

Your manuscript and letter finally have caught up with me in my vacation hideaway in Maine. I am pleased that I was able to read the preprint. It is a most important communication and thrilled me no end. I have not been as excited about a medical article in a long time. For the past five years, I have tried to organize an investigation that will demonstrate the prognostic implications of ventricular ectopic activity. At first, I attempted to do so in Boston and then with HIP in New York [the Health Insurance Plan, an early HMO], but could not persuade the NIH of the importance of such an endeavor. I am pleased that you have carried out these important correlations and done so in such a masterly fashion.

My congratulations to you and the participants in the Coronary Drug Project who have provided us with these vital findings.

On the way back from Geneva, how about stopping over in Boston?

Warm regards,

Bernard Lown, M.D.

* * *

This portion of his pleasant letter, which was followed by a detailed and helpful critique of our article, was the beginning of a short, bittersweet professional relationship with Lown, respected clinical scientist and social activist.

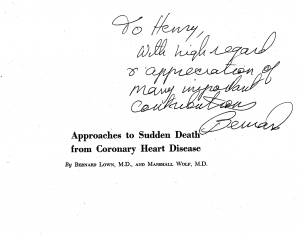

In retrospect, Lown’s letter revealed aspects of his intense personality that I would come to know in greater detail. There was in it a generous outpouring of enthusiasm from the dedicated scientist. He was truly delighted with our findings among many patients, systematically analyzed and in numbers beyond his and others’ clinical experience at the time. Could one also read into Lown’s letter a touch of chagrin over our making these observations, having little experience with, and no tradition of research into electrical instability of the heart. His detailed critique in the letter’s postscript confirms that view. But perhaps I read too much into his kind note. At any rate, he was cordial, and enclosed his latest reprint, flatteringly autographed:

Mission to Moscow

A year or so after this exchange, I received a bolt from the blue, a letter of invitation from Ruth Hegyeli of the International Division of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and executive officer for Group 6 of the U.S.-Soviet Health Treaty, the group concerned with studies of sudden death. This was sent under the chairmanship of none other than Bernard Lown. Most of the other joint study groups with the Soviets were for blood lipid research among the two hostile giants, under the new Nixon policy of “Detente.” Huge energies were poured into collaborating lipid research centers in the Soviet Union and their standardization with the burgeoning research apparatus of the NHLBI Lipid Research Centers in this country, thus contributing to the statistical power and generalizability of the “grand lipid schema” of Fredericksen and Levy. Their far-ranging studies of the relationship of lipids and lipid-lowering strategies to coronary disease risk had top priority at the institute in those days. They had themselves a real winner. Phat!

I was appropriately excited over the prospect of a trip to the Soviet Union under such auspices. Things were moving ahead vigorously in our laboratory in 1973, with the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program, the Lipid Research Center Study, and the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial, all in the competent hands of colleagues. At home, Nelly was happily teaching at Blake School, both daughters were comfortably ensconced in school or college, and son John was busily learning fine millwork in his beloved New Orleans. I took off for Moscow in the fall of 1973 with a light heart and a high sense of adventure.

Our team gathered first in New York, where we were hosted by Isadore Rosenfeld, a cardiologist who has since become a popular medical writer and TV personality. We had a delightful meeting in his charming Fifth Avenue home, a turbulent, merry household. The entire Group 6 team was simpatico, with Lown the leader, Sid Shapiro, Len Cobb, Rosenfeld, and me. Then we were off to Moscow, arriving in that seeming unfriendly place with its scudding skies and threat of winter already in the first week of October. Warm Russian hospitality lived up to its reputation, however, and we met our collaborators from around the Soviet Union in an elegant hall at the Kremlin, tables groaning with smoked sturgeon and salmon, caviar, hard-boiled eggs, soft drinks, beer, and vodka by the liter. Our hosts drank freely and everyone smoked. [There was not yet the Puritanical furor later introduced by Gorbachev against smoking and drinking alcohol at official Soviet receptions.] Our ultimate host was Eugenie Chazov, head of the Myasnikov Cardiology Institute, who was slated to become Soviet Minister of Health. He and our immediate host, Raphael Oganov, chief of preventive cardiology, were everywhere in evidence, toasting our mission at the drop of a hat in the strange new lightness of being that was Détente, with the newfound collaboration among eager medical communities.

Group 6 working sessions were held in the Myasnikov, a drab Soviet structure, yet one full of tradition. Its founder was well known to us in Minnesota from his active blessings on preventive cardiology in international meetings of the 1950s and 1960s. He was highly respected internationally for his observations on the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, and his institute was made up of the elite minds in the country. Not incidentally, Myasnikov was a survivor among the physicians who had attended Stalin at the close of his life, evidence enough of strength and shrewdness.

I felt particularly warmly toward Professor Metelitsa, who at the time was leading descriptive epidemiological studies in the Soviet Union and enthusiastically using the Rose and Blackburn WHO manual on field methods. When I invited him to join us in upcoming international meetings on heart attack survey issues, he subtly let me know that as a “second-class citizen” he was unlikely ever to travel outside the country. Only the grand medical politicos (and Party Members) had such freedom of action, certainly not Jewish intellectuals like himself, who served always under a hanging sword. [It was refreshing to see Professor Metelitsa well and apparently free and happy at a conference in Montreal in 1997.]

By now, the somber Russian winter had set in. We trudged between the Kremlin, the Institute, and our wretched downtown hotel, becoming damp and soiled despite new Cossack lambs-wool hats and plastic raincoats. I sat in our dank hotel room thinking, calculating, and writing for hours on end, looking out on the sad scenes of downtown Moscow: the dark-costumed women street cleaners, the wretched drunks vomiting in the gutter, the ugly flow of streetwalkers and black marketeers parading past our international hotel.

Now that the official treaty celebrations were done, we were reduced to eating greasy borscht and drinking bad beer in the hotel cafeteria. The only bright spot in this drab scene was the warmth and optimism of my roommate, Len Cobb. Len was a pioneer in emergency medicine, resuscitation and survival from sudden death, which he promoted and studied among the population of Kings County, Washington.

Tension Develops in Group 6

Our Sudden-Death Working Group was now in full session and the Russians were presenting what they felt was possible to accomplish in our collaboration. Then Bernie Lown responded with what we felt was necessary for a multi-strategic approach to the problem in the Soviet population: surveys, cohort studies, and recruitment into preventive trials.

It soon became evident that we were dealing with complex political subdepartments of the Moscow community. We learned further that the all-powerful Soviet state was not all that powerful when it came to carrying out surveys. Despite decades of fear and oppression, the individual Soviet citizen of the day was as cantankerous and independent as any being on earth. He or she was inherently and particularly suspicious of state monitors knocking on their apartment doors with questionnaires in hand. Our colleagues could promise only a 50 percent response rate. We were accustomed to 90 percent in Minnesota in those days, the percentage needed for survey validity. This was just one of many incongruities we found in Soviet collectivism.

With questionable assumptions that our work could be done at all, we then started speaking of how it should be done. I made computations of the sample size and power for studies of ectopic cardiac activity in predicting sudden death and for preventive trials, based on frequency estimates of each from our Minnesota studies. Pushing my colleagues, both Russian and American, to make decisions about each component, that is, error assumptions and power, expected frequency of predictors and events and, for trials, treatment effect, lag time to effect, and drop-out rate, it became clear that reasonable statistical power would not be possible within the available local populations, at least under our careful prior assumptions. Neither the chief of our mission nor his Russian counterpart could, however, accept this judgment.

So I began to make more positive sounds, for example, about how we could do a valuable pilot study to demonstrate critical components of the sample-size computations so that we might eventually make more appropriate power estimates for more definitive studies, etc. Our Group 6 principals decreed, nevertheless, that we would forge ahead with firm plans for the grander definitive studies, “Blackburn’s estimates be damned.”

The person I counted on most for confirmation of my figures, the distinguished statistician Sam Shapiro, more politically savvy than I, said little, just shrugged his shoulders. And our other senior colleague, Isadore Rosenfeld, bought entirely into our chief’s plaints that my estimates were “unacceptable.”

As I rounded the corner to enter Lown’s meeting room one afternoon the conversation abruptly hushed. I suddenly recalled Italo Salvo’s truism: “The absent are always wrong.” Out of the room — out of favor.

Soon it was implied that Blackburn’s views on study design and feasibility “risked destroying our joint mission.” I lacked the political acumen to address and resolve the issues diplomatically in face of the perceived political necessity to establish some, nay, any, bipartite U.S.-Soviet study. My function was reduced to pleasant chit-chat with my room mate, Len Cobb.

The Red Arrow Express to Leningrad

Happily, team tension was broken just then by an adventuresome trip on the Red Arrow Express to Leningrad, planned as a diversion for our group. We boarded comfortable wagon-lit accommodations with a sense of excitement and Levantine mystery. Crack express train notwithstanding, it stank of old vodka, urine, bad food, and cheap cigarettes. Late in the evening, in the dining car, I was accosted by the Reverend Ilia Orlov, a garrulous chap who spoke excellent American English and who presented me a business card indicating that he was vice-chairman of the international department of the Baptist Union, pastor and organist of the Moscow Baptist Church. In a lively conversation he sought to convince me that his church was a viable organization under “new Soviet policies for freedom of worship,” and that he himself was free to travel widely, including, voici, on the Red Arrow Express. He was happy to inform me, moreover, that his accommodations were immediately next to mine.

Some time later, our Russian colleagues confirmed my skepticism. No head of an evangelical denomination in Soviet lands had any such freedoms in those times. They assumed that the gentleman assigned to the next compartment to mine was an agent of the KGB. And they volunteered further that the KGB must have a file on each of us U.S. delegates; else why was this preacher type delegated to make contact with me? Perhaps the paranoia epidemic in Stalin’s land is contagious.

Sunny Leningrad was uplifting after soggy Moscow: the elegance of The Hermitage paintings and artifacts contrasted with the powerful Siege Museum, where Leningrad’s courageous resistance to the long German siege in World War II was portrayed.

During the tour, our attractive Intourist guide let us know subtly as time went on that she was Jewish and had been waiting for some years for an exit visa to America or Israel. I somehow determined that she spoke French and for much of the first day, during relaxed moments between events, we would chat in French. The next morning she became quite severe with me, saying sternly, “Now, Dr. B., please speak only English with me.” I learned later that our KGB monitor could not understand our speaking in French, had become suspicious, and had put her on notice. Of course, I obliged her.

After the light of Leningrad [happily, now again called St. Petersburg, if unhappily, also called City of Crime], we returned to the gloom of Moscow for the closing diplomatic festivities.

The Saturday Night Massacre

During the Group 6 meeting on the next-to-last scheduled day in Moscow, we were interrupted by a hush-hush visit from an agitated, somber-faced young foreign service officer from our American embassy. He informed us of the “Saturday Night Massacre” back home and the resignation of Attorney General Elliot Richardson over Nixon’s insistence that he fire Archibald Cox, special prosecutor of Watergate. Then our Consul messenger uttered even more chilling news: “It appears that President Nixon has ordered a full world wide armed forces alert. We will keep you informed as to how this might affect your departure from the Soviet Union.”

We looked at each other dumbfounded, some of us recalling the horror stories of people trapped in American missions around the world when doors slammed shut at the outbreak of World War II. Nixon, we speculated, in fall, 1973, was not beyond starting World War III to resurrect his crumbling power.

The next day we were all edgy as we waited for hours, first in our hotel and then in the holding area of Moscow airport, for our diplomatic clearance to leave the Soviet Union. We were reassured when we saw the soon-to-be minister of health, our friend Chazov, circulating among the officials responsible for our detention and processing. Finally, we were allowed to board, our relief at getting away from that oppressive land greater than our anxiety over flying in the grubby, creaky Tupelov aircraft. The ancient jet seemed to require an interminable takeoff run and then to grapple skyward at a pitifully flat angle. But eventually we were high in the heavens, vodka and sandwiches were served, and we smugly looked down at Minsk and then Warsaw as we happily wended our way westward.

On touching down in London, some of us literally, and all of us figuratively, kissed the free Western soil of England. In the company of a cheerful colleague from the London School of Hygiene, Fiona Stanley, our freedom-starved group enjoyed a convivial, almost rowdy meal in the brilliant intellectual capital of the West.

Sequel #1

A major early undertaking of my new direction of the Lab in the 1970s was a research program on ventricular ectopic activity and sudden death, about which Ron Prineas and I organized the Spring Hill Conference on Sudden Death in fall of 1974. Bernie Lown, at first reluctant, was eventually persuaded to come, I suspect by the fact that we had gotten every other major figure in the field aboard. We were giving a thorough treatment to the topic, with bench, clinical, and epidemiological contributions. I caught Lown shaking his head negatively on several occasions during my presentations when, by this time, I was convinced that we had not been able to demonstrate by our statistical approaches the independent prognostic power of ectopic rhythms for sudden death, at least when using ordinary electrocardiograms and Holter monitoring. We concluded that such observations of excess risk, though interesting, were hopelessly confounded by other attributes of the ischemic myocardium. That skeptical conclusion, based on limitations of the epidemiological data, reflected not a whit on Lown’s excellent physiological and clinical evidence and broad syntheses on the issue. Nevertheless, he vigorously, pointedly, and publicly rejected our conclusions from our own data.

Lown’s early letter to me (quoted in part above) had closed with the following criticism of our study of ectopic beats in CDP post-infarction patients: “You state a number of oft-repeated truisms but do not address yourself cogently to the fact that many CHD deaths are accidental, that is, sudden, for which we already have the means of prevention, if the victim could be precisely identified.” [my italics] Clearly, Lown and I continued to have a language barrier more serious than the usual barrier among practitioners of separate research disciplines, bench, clinical, and epidemiological.

Lown’s grand scheme to prevent sudden death among those “precisely” identified as vulnerable, along with other aspects of that issue, were discussed fruitfully at the Spring Hill Conference, and subsequently reported in a presumably useful Sudden Death supplement to Circulation.1 His foresighted scheme only really took off many years later when “precise” electrophysiologic measures of vulnerability, coupled with the automatic implantable defibrillator (first presented in detail at Spring Hill in 1974), became practical realities. Meanwhile, simple if inefficient measures of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and augmented emergency services, tested widely in the public educational programs of Len Cobb in Seattle, had a powerful impact throughout the medical and lay community, saving untold numbers of lives.

In a 1976 meeting arranged by Len Cobb in Seattle, I presented my summation of some years of work on this issue, including controlled trials performed with Guy DeBacker on physical conditioning in attempts to reduce ectopic rhythms. It was a pleasant occasion there under Cobb’s kind and thoughtful hosting.

Not long afterward, the intense private conversations between Chazov and Lown, which had gone on during our visit to Moscow in 1973, and which we learned later had nothing to do with sudden death but with the threat of nuclear annihilation, resulted in the Nobel Peace Prize being awarded to the organization called Physicians for Social Responsibility, headed by none other than Bernard Lown in Boston and Eugenie Chazov in Moscow!

I have not followed up whether joint studies were ever completed from our mission about sudden death. All things considered, however, the efforts of the U.S.-Soviet Health Treaty, Group 6 on Sudden Death, had, it seems, paid off.

Twenty-five years have passed since I saw Bernie Lown. I was intrigued to read his letter to The New Yorker of May 1999, in which he pleaded for more medical-pharmaceutical management of coronary artery disease in contrast to today’s emphasis on surgical bypass grafts and other direct interventions. I thought I might write asking him whether he, even now, sees no advantage to survival from lifestyle changes as well as from drugs. Somehow, I never got the letter off.

Sequel #2

In fall, 1976, the European Congress of Cardiology met in Amsterdam, where it was hosted by the talented and flamboyant Paul Hugenholz and his charming wife, Josephina. For the grand gala of that meeting, our host had arranged a colorful live exhibit of old Dutch guild halls around a large periphery, and in a central gazebo was a jazz band, designed, he claimed, for my participation. After parades with jazz band and clowns and balloons and other delightful foolishness, the hall was cleared for serious dancing. My companion for the evening was my 21-year-old daughter, Katia, whose biking tour of Europe we had planned to intersect my itinerary. She was young, blond, and beautiful, with long tresses flowing to her thighs. It seemed to me, proud Papa, that we made a happy and elegant couple dancing.

As we waltzed about, I caught sight of several of our old Group 6 Moscow colleagues on the sidelines and during a pause in the dance we strolled by them. One whispered in my ear, “Congratulations on your young wife, Henry.” I laughed and assured him that Katia was rather my darling daughter. The very next dance, a tall, handsome young Russian appeared at my elbow, requesting to break in and dance with Katia. With her permission, I gracefully yielded and made my way toward the sidelines. There one of the Soviet delegates spoke again in my ear, telling me that my daughter’s dancing partner was none other than the KGB monitor for the entire Soviet medical delegation to the World Assembly!

I let my Russian colleagues know in certain terms how happy I was that they wanted to help entertain my daughter but how unhappy that they chose the KGB to do it. If you please!

1) Prineas R, Blackburn H (editors). Sudden coronary death outside hospital. Circulation 52, Suppl. III; 287 pp., December, 1975.